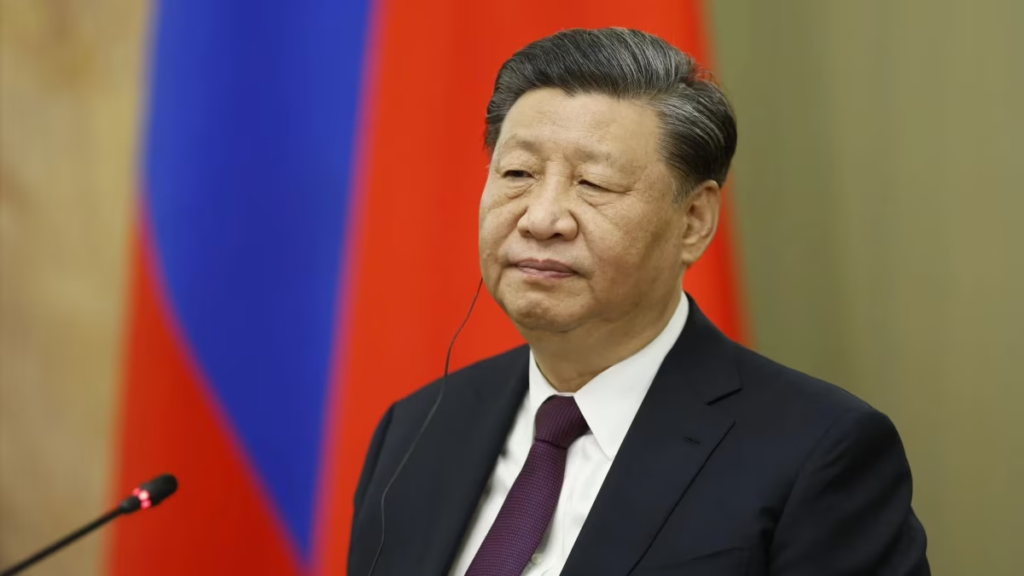

China builds 200 new prisons in the wake of an intensified anti-corruption campaign led by President Xi Jinping, marking a significant escalation in the country’s efforts to root out corruption.

These new facilities, known as “liuzhi” centres, are part of a broader strategy to extend the reach of the Chinese Communist Party’s power, targeting individuals suspected of engaging in corruption or exercising “public power.”

With construction ramping up in the years following the pandemic, China’s expansion of its prison system raises numerous legal, ethical, and human rights concerns, while further consolidating Xi Jinping’s hold on power.

The creation of these 200 new detention facilities aligns with the broader goals of Xi’s anti-corruption drive, which has been a defining feature of his leadership since coming to power in 2012.

However, the methods used in detaining suspects, coupled with allegations of abuse and forced confessions, have led to increasing scrutiny from both domestic and international critics. This blog explores the construction of these new prisons, the issues surrounding the liuzhi system, and the broader implications of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption policies.

The Liuzhi System: A Tool for Political Control

The establishment of the liuzhi detention centres represents a shift in China’s approach to anti-corruption efforts. Codified in 2018, the liuzhi system replaced the controversial “shuanggui” system, which was heavily criticized for its use of torture, abuse, and the widespread violation of detainees’ rights.

Liuzhi centres are described as more “civilized” in comparison, designed with padded walls, anti-slip surfaces, and 24/7 surveillance, but critics argue that these facilities still enable a system ripe for exploitation and abuse.

The liuzhi centres are built for the detention of suspects without access to legal counsel or family visits, allowing them to be held for up to six months without formal charges or the presence of a lawyer.

Read : Man Who Drove Car into a crowd Outside Primary School in China Sentenced to Death

This creates a vacuum of oversight, giving authorities wide discretion to detain individuals for extended periods, often under extreme conditions. These centres are not limited to party members or government officials; they also target private sector figures, such as businesspeople accused of bribery or other forms of corruption.

Read : China Creates Chat Xi PT: AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping’s Ideas

Over the past seven years, more than 218 liuzhi centres have been built or expanded, with a notable acceleration in construction following the pandemic. The national plan for constructing these facilities, which runs from 2023 to 2027, indicates that the expansion of the detention regime is only set to grow.

These centres are seen as central to Xi Jinping’s broader anti-corruption strategy, which is not only aimed at rooting out graft but also at consolidating his political control by ensuring the loyalty of all sectors of society.

Concerns Over Abuse and Forced Confessions

While the government argues that the liuzhi centres represent a more humane approach to detention, numerous reports indicate that these facilities are still rife with abuse.

Detainees, including high-profile figures such as billionaire investment banker Bao Fan and former soccer star Li Tie, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for corruption, often face intense psychological pressure, physical abuse, and torture.

A lawyer representing officials in corruption cases shared with CNN that most detainees subjected to the liuzhi system “succumb to the agony,” underlining the extent to which such detention can break individuals mentally and physically.

One chilling account comes from former official Chen Jianjun, who was subjected to extreme sleep deprivation and forced to endure grueling daily routines during his six-month detention. Chen’s account, which was shared by his daughter, described how he was forced to sit upright for 18 hours each day, as well as the physical and mental toll it took on him.

His claims were further supported by sketches he made on toilet paper, detailing the harsh and inhumane conditions within the liuzhi centre. Such reports have raised alarm about the lack of oversight, as these facilities operate outside the boundaries of China’s normal judicial system.

The fear of torture and abuse under the liuzhi system has sparked growing concerns among both domestic and international observers. Critics argue that the centres enable the abuse of power and have been used by local anti-graft agencies to detain businesspeople and extract bribes under false pretenses.

A now-censored article by economist Zhou Tianyong also warns that such practices could potentially harm China’s economy, as the system’s unchecked powers create an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty, discouraging entrepreneurship and economic growth.

The Legal and Political Implications

The expansion of the liuzhi system has sparked a heated debate in China about the balance between effective anti-corruption measures and individual rights. While the government insists that these measures are necessary to maintain social stability and ensure the long-term health of the economy, critics argue that they undermine the rule of law and human rights.

In 2024, a proposed amendment to the national supervision law has added to this debate, mandating investigators to follow “lawful, civilized, and standardized” interrogation practices.

However, the amendment has also stirred controversy by failing to address the demand for legal counsel during the liuzhi detention process, effectively leaving detainees vulnerable to coercion and forced confessions.

Furthermore, the proposed amendment suggests extending the maximum detention period from six to eight months, giving authorities even more time to extract information from detainees without the presence of legal representation.

Such amendments only serve to reinforce fears that the Chinese legal system is increasingly being used as a tool of political control, with the anti-corruption campaign serving as a pretext for suppressing dissent and consolidating power in the hands of Xi Jinping and the Communist Party.

At the heart of this debate is the question of whether the measures taken by the government are truly in the service of justice and national stability or if they are being wielded as a political tool to eliminate opponents and stifle criticism.

For many, the growth of the liuzhi centres represents an erosion of China’s legal safeguards, while others argue that the country’s fight against corruption justifies the expansion of such measures, however harsh they may seem.

The Dangers of an Expanding Detention System

China’s decision to build and expand more than 200 liuzhi centres is a clear sign that President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign shows no signs of abating.

While these facilities may be designed to combat graft and ensure greater control over Chinese society, they also raise significant concerns about the abuse of power and the erosion of individual rights.

Detainees face immense psychological pressure and physical abuse in environments where they are denied basic legal protections and human rights.

As the construction of these centres continues at an accelerated pace, critics argue that the Chinese government’s efforts to eliminate corruption may have unintended consequences, particularly as the system allows for the abuse of power and the silencing of political dissent.

The expanded detention regime also poses a risk to China’s economy and its international reputation, as businesspeople and foreign investors may be discouraged by the lack of legal transparency and the constant threat of arbitrary detention.

The issue of liuzhi centres ultimately highlights the tension between maintaining political control and upholding the rule of law. As China’s anti-corruption drive intensifies, it is crucial to question whether the methods used to fight graft will ultimately lead to greater corruption within the system itself, undermining the very principles they are meant to protect.