In a story that has gripped the nation and sparked widespread heartbreak across social media, a two-year-old boy nicknamed Mianmian endured unimaginable isolation in a tiny rented room in southeastern China after his young mother tragically passed away. Left without adult supervision, the toddler scavenged for survival amid a clutter of everyday items, relying solely on whatever edible scraps he could reach. This incident, unfolding in the quiet county of Cangnan in Zhejiang province, underscores the fragility of single-parent households and the silent struggles many families face in modern China.

The discovery came on August 17, when a concerned friend of the mother, unable to contact her for several days, alerted police to check on the family. Officers arrived at the modest rental flat in Wenzhou’s Cangnan county, a coastal area known for its fishing communities and growing migrant worker population. Inside the cramped 10-square-meter bedroom, they found 28-year-old Zheng Yu deceased, her body amid the disarray of bedding, clothes, and household odds and ends.

Beside her, huddled and frightened but alive, was her son Mianmian, who had been fending for himself in the confined space for an estimated three to four days—though the exact timeline remains under investigation as forensic experts piece together the sequence of events. Zheng, a single mother, had been living a low-profile life in the area, far from her hometown, scraping by on odd jobs that barely covered rent and basic necessities. Neighbors later recalled her as a quiet, devoted parent who kept to herself, occasionally seen carrying groceries or playing with Mianmian in the hallway of their rundown apartment building.

The room itself was a snapshot of survival: piles of unwashed laundry, scattered toys, and a small kitchenette with minimal supplies. No signs of foul play were immediately evident in Zheng’s death, which authorities believe stemmed from natural causes possibly exacerbated by underlying health issues she may have kept private. An autopsy is ongoing to confirm the cause, but initial reports suggest it was sudden and painless, sparing her the awareness of the ordeal her son would face in her absence.

Read : 22 Year Old Kameron McMaken Shot Dead His Father During an Argument

Mianmian, barely out of diapers and still mastering basic words, presented a heartbreaking picture to the responding officers. Covered in grime and wearing the same clothes from days prior, the child was dehydrated but alert, his wide eyes reflecting confusion rather than panic.

Read : why people celebrate new year on 31st December instead of 1st January ?

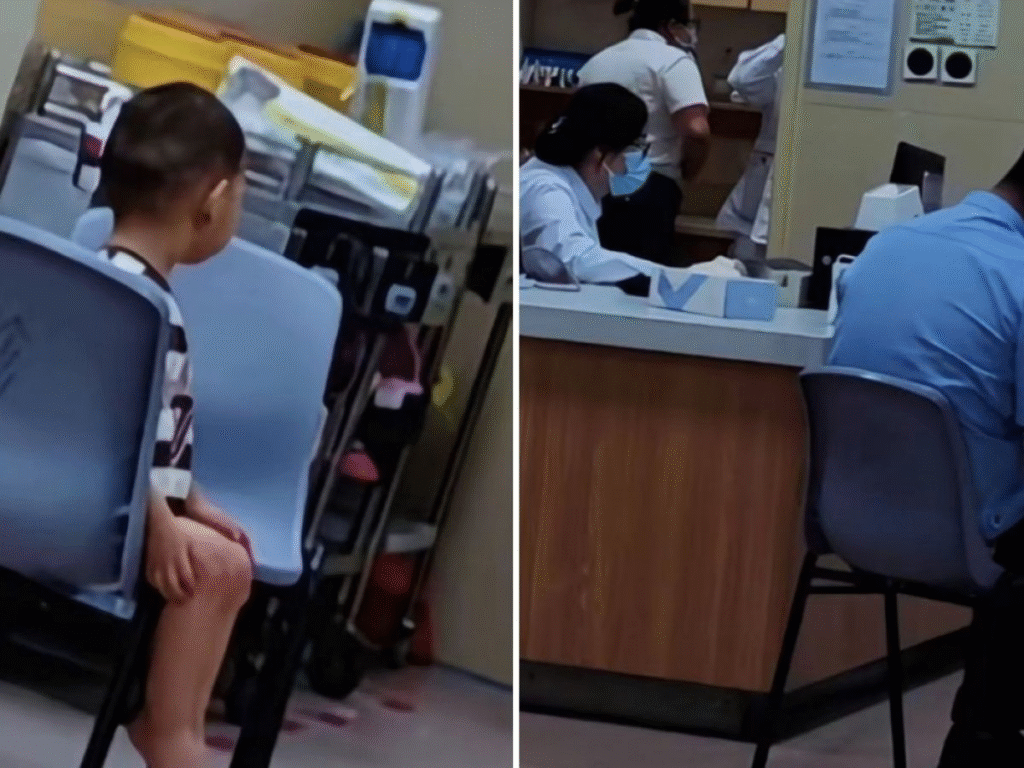

Paramedics rushed him to a nearby hospital in Wenzhou for evaluation, where doctors noted minor nutritional deficiencies but marveled at his overall stability given the circumstances. “He was lucky,” one pediatrician involved in his care told local media, emphasizing that at his age, prolonged isolation could have led to rapid deterioration. Yet, in the face of such odds, Mianmian’s story is one of unwitting fortitude—a tiny human navigating crisis through instinct alone.

The Tiny Room: A Battlefield of Survival

Delving deeper into the confines of that 10-square-meter space reveals the raw ingenuity of a child’s desperation. The bedroom, barely larger than a walk-in closet, served as the family’s entire living quarters—a common reality for low-income renters in China’s densely packed urban fringes. Walls papered in faded floral patterns bore witness to the chaos: overturned stools, spilled packets of instant noodles, and a single window shrouded by heavy curtains that dimmed the summer light. It was here, surrounded by his mother’s belongings, that Mianmian pieced together his sustenance from the detritus of daily life.

The toddler’s diet, pieced together from police observations and later medical assessments, was a haphazard assembly of junk food and oddities within arm’s reach. Jellies, those colorful, gelatinous treats popular among Chinese children for their fruity flavors and easy chew, formed the bulk of his calories—wrappers littering the floor like confetti from a forgotten party. Scattered bags of savory snacks, likely potato chips or puffed rice crisps bought in bulk from a nearby market, provided crunch and salt, though their nutritional void offered little beyond fleeting energy.

One poignant detail emerged from the scene: a half-gnawed pumpkin, its orange flesh marked by tiny, uneven bites, suggesting Mianmian had tugged it from a shelf or corner, using his small teeth to access its fibrous interior. Herbal tea bags, steeped haphazardly in a spilled cup, added a bitter note to his improvised meals, perhaps the only liquid he could manage without running water skills beyond his grasp.

Experts in child survival, consulted post-incident by Zhejiang health officials, explain that Mianmian’s ability to last days without proper care hinged on these accessible items. At two years old, a child’s metabolism burns through energy quickly, but the sugar highs from jellies likely sustained bursts of activity, preventing total collapse. The pumpkin, rich in vitamins despite its raw state, inadvertently balanced the junk’s excesses, averting severe vitamin deficiencies.

Yet, the psychological toll is harder to quantify. Psychologists note that toddlers in isolation often regress to self-soothing behaviors—rocking, thumb-sucking, or clutching familiar objects—which Mianmian exhibited upon rescue, clinging to a worn stuffed bear amid the mess. The room’s clutter, while chaotic, may have shielded him from harm; no sharp edges or hazards were reported that could have compounded his plight.

This microcosm of survival paints a stark portrait of poverty’s grip. Zheng’s home lacked the safety nets many take for granted: no stocked fridge, no emergency contacts prominently displayed, no community watch that noticed the silence from the unit. In Cangnan, where migrant families like theirs swell the population, such isolation is not uncommon.

Local welfare reports indicate that single-parent households, comprising nearly 15% of the county’s underprivileged demographic, often fall through cracks in monitoring systems designed for larger families. Mianmian’s ordeal, confined to that suffocating square footage, amplifies the urgency for micro-interventions—door-to-door checks or app-based welfare alerts—that could bridge such gaps.

Echoes of Resilience and a Mother’s Shadow

At the heart of this tragedy lies Mianmian himself, a symbol of unyielding human spirit wrapped in the innocence of toddlerhood. Born in 2023 to Zheng, who navigated motherhood solo after an undisclosed separation, the boy was described by acquaintances as “cheerful and curious,” traits that perhaps fueled his endurance. Hospital records from his admission show a child weighing just under 12 kilograms—average for his age—but with elevated stress markers in his bloodwork, hinting at the cortisol-fueled vigilance of those lonely days.

Nurses recount how he initially recoiled from touch, associating adults with absence rather than comfort, but warmed quickly to gentle coaxing, downing bowls of proper porridge with wide-eyed relief. Zheng’s life, glimpsed through fragments shared by her friend who raised the alarm, was one of quiet perseverance shadowed by hardship. At 28, she had migrated from a rural inland province to Zhejiang’s bustling coast, chasing factory work that promised stability but delivered grueling shifts and meager wages. Friends recall her pride in Mianmian, posting rare photos on WeChat of park outings or homemade meals, always captioning with emojis of hearts and smiles.

Yet, beneath the surface, financial strains mounted: unpaid bills piled up, and health woes—rumored to include chronic fatigue—sapped her vitality. She had no immediate family nearby; her parents, elderly farmers back home, were too distant to intervene. In China’s evolving social fabric, where the one-child policy’s legacy lingers in altered family structures, Zheng embodied the unsung millions balancing parenthood with precarious employment. Her death, likely from an undiagnosed cardiac event given her age and stress levels, robbed Mianmian of that anchor, thrusting him into a void no child should know.

The rescue’s aftermath unfolded with quiet efficiency. Police, trained in child welfare protocols, prioritized Mianmian’s handover to state care. He was placed in a temporary foster home in Wenzhou, where caregivers report he’s thriving—gaining weight, babbling new words, and forming bonds with a rotating team of social workers. Relatives from Zheng’s hometown have come forward, vying for custody in a process that could span months under China’s family court system.

Investigations cleared the friend of any negligence, praising her vigilance instead. For Mianmian, therapy sessions focus on rebuilding trust, using play-based techniques to process the unspoken trauma. “He’s a fighter,” his caseworker said, echoing sentiments from the medical team. In a nation where child resilience stories often go viral, Mianmian’s has resonated deeply, with online forums buzzing about “little warriors” and the need for guardian angels in every block.

China’s Wake-Up Call: Safeguarding the Vulnerable

This heartrending episode has reverberated far beyond Cangnan’s shores, igniting a firestorm of discourse on China’s social safety nets. On platforms like Weibo and Douyin, hashtags surrounding the story have amassed millions of views, blending grief with outrage. Users share personal anecdotes of overlooked neighbors, demanding reforms like mandatory welfare check-ins for single-parent units or subsidized daycare expansions.

“How many Mianmian are out there, silent in the shadows?” one viral post queried, capturing the collective anguish. Pundits in state media, from People’s Daily to Zhejiang Online, frame it as a litmus test for the government’s “common prosperity” agenda, which pledges to uplift the marginalized amid economic slowdowns. Experts weigh in on systemic fixes. Child welfare advocates, citing statistics from the Ministry of Civil Affairs—over 700,000 children in non-traditional families nationwide—push for AI-driven monitoring apps that flag unusual patterns, like prolonged inactivity on utility accounts.

In urbanizing areas like Wenzhou, community grids—neighborhood watch programs—could be bolstered with training on spotting isolation cues, from uncollected mail to children’s unaccompanied cries. Economically, calls grow for wage floors in gig sectors where mothers like Zheng toil, ensuring access to health screenings that might have detected her vulnerabilities early. Internationally, the tale draws parallels to global child protection debates, underscoring China’s unique pressures from aging populations and rural-urban divides.

Yet, amid the policy clamor, hope flickers in human kindness. Donations pour into verified funds for Mianmian’s care, while volunteers organize toy drives for foster kids in Zhejiang. Zheng’s friend, now a makeshift advocate, speaks at local forums, her voice steady: “She loved him fiercely; we must honor that by building a safer world.”

As investigations wrap and Mianmian toddles toward a new chapter, his survival stands as both indictment and inspiration—a call to weave tighter the threads of community, ensuring no child faces the void alone. In the end, this is more than a tragedy; it’s a catalyst, urging China to nurture its smallest citizens with the vigilance they deserve.