In a landmark decision that underscores systemic failures in child welfare, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors has approved a $20 million settlement to the family of Noah Cuatro, a 4-year-old boy from Palmdale who endured months of horrific abuse before his death at the hands of his parents in 2019. The approval, finalized on September 30, 2025, comes six years after Noah’s tragic passing and follows a wrongful death lawsuit that exposed repeated lapses by county child protective services. This payout represents one of the largest settlements in recent history for a case involving child abuse oversight, highlighting ongoing concerns about the county’s ability to safeguard vulnerable children.

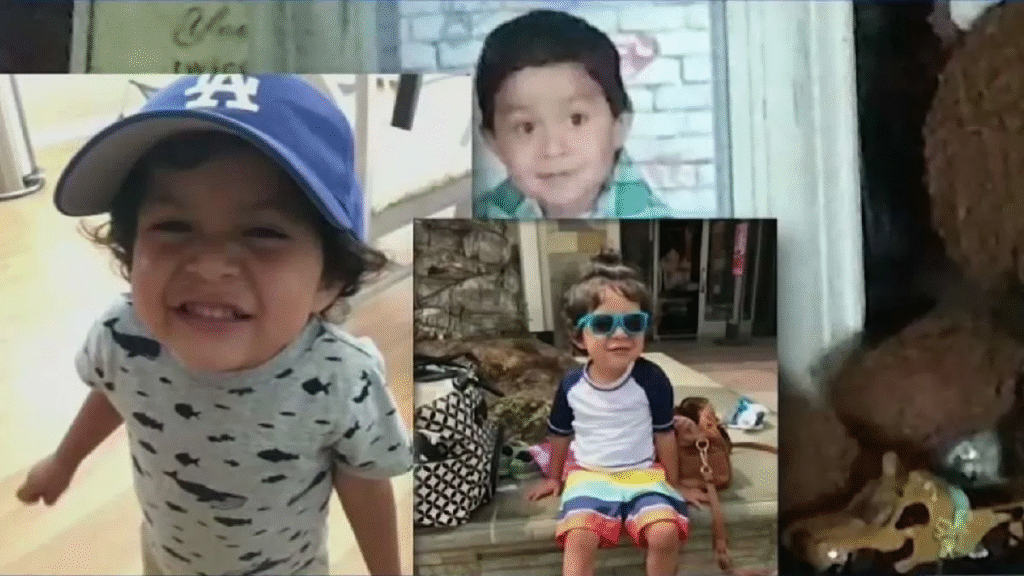

The case of Noah Cuatro has long served as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences when reports of abuse go unheeded. Noah, described by relatives as a bright and affectionate child, suffered unimaginable torment in the final months of his young life. His parents, Jose Maria Cuatro Jr., 33, and Ursula Elaine Juarez, 32 at the time, were convicted in 2022 of first-degree murder and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison without parole.

Prosecutors detailed a pattern of brutality that included beatings with belts, cords, and fists; deliberate starvation; and immersion in scalding water, leaving Noah with burns, bruises, and emaciated limbs. An autopsy revealed he weighed just 30 pounds at death—half the average for his age—and had sustained multiple fractures and internal injuries consistent with prolonged torture.

Noah’s death occurred on July 6, 2019, just days shy of his fifth birthday. His parents initially claimed to authorities that he had drowned in the family bathtub, but medical examiners quickly debunked this narrative. The official cause of death was ruled as homicide by blunt force trauma, compounded by malnutrition and dehydration. The couple’s other children—siblings to Noah—were also removed from the home and placed in protective custody, revealing a household rife with violence and neglect. Court records from the criminal trial painted a chilling picture: neighbors and family members had witnessed Noah’s deteriorating condition, with visible welts and a gaunt frame that screamed for intervention.

The County’s Repeated Oversights in Protecting Noah

At the heart of the civil lawsuit filed by Noah’s great-grandmother, Eva Hernandez, and other relatives was the allegation that Los Angeles County’s Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) ignored at least 14 separate abuse reports spanning two years. These referrals came from mandatory reporters—teachers, medical professionals, and even relatives—who flagged concerns as early as 2017. One particularly damning report in February 2019 described Noah arriving at school with a black eye and cigarette burns on his arms, yet DCFS deemed the explanation from his parents—that he had fallen—credible enough to close the case without further action.

Attorneys for the family argued in court filings that DCFS workers failed to conduct thorough home visits, interview collaterals like school staff, or escalate the matter to higher-risk protocols despite the accumulating evidence. A key example involved a March 2019 incident where Noah was hospitalized for severe malnutrition; hospital staff notified DCFS, but the department opted for a “voluntary family maintenance” plan rather than removal. This decision allowed the abuse to escalate unchecked. Internal reviews later admitted that the case was “mishandled,” with workers overburdened by caseloads exceeding 100 families each, a chronic issue plaguing the county’s child welfare system.

The lawsuit, filed in 2020 in Los Angeles County Superior Court, sought damages for negligence, wrongful death, and emotional distress. It contended that had DCFS acted decisively, Noah’s life could have been saved. Discovery in the case unearthed emails and logs showing that supervisors dismissed red flags as “unsubstantiated,” prioritizing family reunification over immediate safety—a policy critics say tilts too far toward leniency. Hernandez, who had repeatedly pleaded with authorities to remove Noah from the home, testified during depositions about her futile efforts, including driving to the DCFS office with photos of Noah’s injuries. “I begged them,” she recounted in a 2023 hearing. “They said they would look into it, but nothing happened.”

This wasn’t an isolated failure. The Noah Cuatro case echoed other high-profile tragedies in Los Angeles County, such as the 2013 death of 8-year-old Gabriel Fernandez, which prompted a $2.75 million settlement and sweeping reforms. In Noah’s aftermath, the county implemented mandatory training on recognizing non-accidental injuries and reduced caseloads by hiring additional social workers. However, a 2024 state audit found that DCFS still struggles with response times, with over 30% of high-priority referrals taking more than 24 hours to assign—a delay that can prove fatal.

Read : 161-Million-Year-Old World’s Largest Stegosaurus Skeleton Put on Auction in New York

Legal experts view the Cuatro lawsuit as a catalyst for accountability. “This settlement isn’t just compensation; it’s a reckoning,” said one child advocacy attorney involved in similar cases. The county’s defense, led by the Office of County Counsel, maintained that while errors occurred, the parents’ actions were unforeseeable. Yet, presiding Judge Mitchell L. Beckloff, in denying a motion to dismiss in 2022, ruled that the evidence demonstrated “gross negligence” sufficient to proceed to trial. Mediation efforts stretched over months, culminating in the board’s unanimous vote to approve the payout, avoiding a potentially costlier jury verdict.

Reactions to the Settlement and Path Forward for Child Welfare

The $20 million settlement, to be distributed among Hernandez and Noah’s surviving relatives, has elicited a mix of grief, vindication, and calls for reform. At the board meeting, Hernandez clutched a framed photo of Noah, tears streaming as she addressed supervisors: “This money doesn’t bring my baby back, but maybe it saves another one.” Supervisor Kathryn Barger, whose district includes Palmdale, acknowledged the “heartbreaking tragedy” and pledged to bolster DCFS resources. “We must do better,” Barger stated, announcing an additional $5 million allocation for child welfare training in the upcoming fiscal year.

Advocacy groups hailed the decision as a milestone. The Los Angeles County Child Care Resource Center, which supported the family pro bono, described it as “a step toward justice for children lost to bureaucracy.” Data from the center shows that California sees over 150 child fatalities annually from abuse or neglect, with Los Angeles County accounting for nearly 20%—a statistic that underscores the urgency of systemic change. The settlement funds will partly support a memorial scholarship in Noah’s name for foster youth pursuing higher education, a initiative spearheaded by Hernandez to honor her great-grandson’s memory.

Critics, however, question whether financial penalties alone suffice. Assemblymember Luz Rivas, who authored legislation inspired by the Gabriel Fernandez case, renewed pushes for statewide caseload caps and AI-assisted risk assessment tools. “Settlements are Band-Aids on a gaping wound,” Rivas said in a statement. “We need proactive prevention, not reactive payouts.” The county, facing a ballooning budget deficit, absorbed the cost from its self-insurance reserves, but officials warn that rising litigation could strain services further.

For the Cuatro family, closure remains elusive. Noah’s siblings, now thriving in stable homes, bear invisible scars from the ordeal. Hernandez has become an outspoken advocate, testifying before the state legislature on DCFS shortcomings. “Every child reported abused deserves a thorough investigation,” she insists. The settlement, while monumental, amplifies a broader narrative: in a county of 10 million, where poverty and addiction fuel family crises, protecting the most innocent demands vigilance beyond bureaucracy.

As Los Angeles County navigates this payout, the Noah Cuatro case endures as a somber benchmark. It compels reflection on the frayed safety net for children and the moral imperative to mend it. In the words of one supervisor during the vote: “Noah’s story must not be forgotten—it must be the reason we change.”