In a somber development that underscores the enduring pain of a tragic crime, Texas carried out the execution of Blaine Milam on September 25, 2025, for the brutal 2008 murder of his girlfriend’s 13-month-old daughter, Amora Carson. The case, which shocked the rural East Texas community of Rusk County, revolved around a horrific 30-hour ordeal prosecutors described as a twisted “exorcism” to expel a supposed demon from the infant’s body.

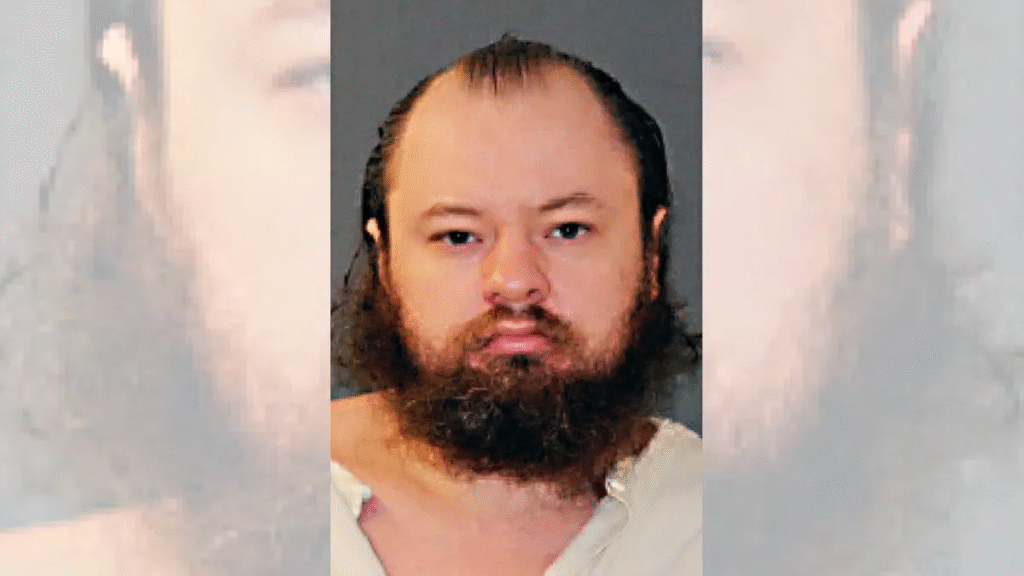

Blaine Milam, who was 18 at the time of the killing, maintained his innocence until the end, blaming his then-girlfriend Jesseca Carson and pointing to flaws in the evidence used against him. His death by lethal injection at the Huntsville Unit prison marks the latest chapter in a story that has haunted families, legal experts, and advocates for more than 16 years. As the nation grapples with questions of justice, faith, and forensic reliability, this execution serves as a stark reminder of the irreversible consequences of capital punishment in America.

The events of December 2008 unfolded in a small trailer home just outside the town of Tatum, a quiet rural enclave near the Louisiana border. Milam and 18-year-old Jesseca Carson, Amora’s mother, were young and living together in what neighbors later described as an isolated, unstable household. On the evening of December 2, Milam made a frantic 911 call, claiming he had just discovered the toddler lifeless in her crib.

Emergency responders arrived to a scene of unimaginable horror: the 13-month-old’s tiny body bore the marks of savage abuse, including multiple skull fractures, broken arms and legs, shattered ribs, and a constellation of bite marks across her flesh. The autopsy revealed that Amora had suffered blunt force trauma consistent with repeated beatings over an extended period, leading to internal bleeding and organ failure.

Initially, the couple’s stories to investigators were inconsistent and bizarre. They first claimed they had left Amora alone in the trailer for about an hour while running errands, only to return and find her unresponsive, possibly from ingesting insulation material from the walls. As police separated them for questioning, the accounts shifted dramatically. Carson tearfully recounted how Milam had convinced her that the baby was possessed by a demon, a malevolent spirit that “God was tired of” because the child had been “lying” to him—a delusional rationale that defied logic for such a young victim. According to court records, Milam allegedly instructed Carson that an exorcism was necessary to save Amora’s soul, initiating a nightmarish ritual that lasted nearly 30 hours.

Read : 13-Year-Old Afghan Boy Survives Perilous 94-Minute Flight in KAM Air Wheel Well from Kabul to Delhi

Eyewitness accounts from the trial painted a picture of unrelenting violence. Blaine Milam reportedly slammed the infant against walls, struck her repeatedly with his fists, and bit her on the arms, legs, and torso in what he claimed were attempts to “cast out” the evil. Carson, torn between her role as mother and her fear of Milam, participated by holding the child down at times, though she later insisted she was coerced.

Read : How To live Life Happily According To Bhagavad Gita

The ordeal only ended when Amora stopped breathing, her small body finally succumbing to the cumulative trauma. Prosecutors argued that the “exorcism” was nothing more than a cover for sadistic abuse, with Rusk County District Attorney John Jimerson stating at the time that no clear motive existed beyond the couple’s need to conceal their actions. The discovery of the child’s battered remains prompted swift arrests, setting the stage for one of the most disturbing capital murder cases in Texas history.

The Trial and Conflicting Narratives

Blaine Milam’s trial in 2011 became a battleground of conflicting testimonies, forensic evidence, and questions about religious delusion. Held in the Henderson County Courthouse, the proceedings drew national attention for their grotesque details and the defense’s portrayal of Milam as a scapegoat in a shared psychosis. Milam, now 21, pleaded not guilty, steadfastly blaming Carson for initiating the violence.

He testified that she had burst into religious fervor, insisting Amora’s face distorted into demonic shapes due to her own untreated neurological condition—a visual-perception disorder that allegedly caused her to hallucinate malevolent features in the baby’s innocent expression. Milam’s attorneys argued that Carson’s religious delusions, compounded by possible postpartum issues, drove the attack, and that he had only tried to intervene. Carson, tried separately, corroborated parts of this narrative in her own testimony but ultimately pointed the finger back at Milam.

Under cross-examination, she revealed how he had proclaimed the child’s possession, citing biblical passages out of context to justify the “exorcism.” “He said God told him she was lying, that the devil was in her,” Carson recounted, her voice breaking as she described the bites and blows she witnessed but failed to stop. The prosecution dismantled these defenses by highlighting the physical evidence: DNA traces under Amora’s fingernails matched Milam’s, and the bite marks—analyzed by forensic odontologists—were deemed consistent with his dental impressions. Witnesses, including first responders, described the trailer’s chaos, with bloodstains on the floor and walls corroborating the prolonged assault.

The jury, after deliberating for less than two days, convicted Milam of capital murder in the course of injury to a child. During the punishment phase, prosecutors emphasized the premeditated nature of the torture, arguing that the 30-hour duration showed deliberate intent rather than a momentary lapse. Milam’s defense called psychologists to testify about his own troubled upbringing—marked by poverty and exposure to fundamentalist beliefs—but it failed to sway the panel.

On May 20, 2011, they sentenced him to death, a verdict that reflected Texas’s aggressive stance on crimes against children. Carson, convicted of capital murder as a party to the offense, received life without parole, her youth and lesser role cited as mitigating factors. The trial exposed deep fissures in how society views mental health, religious extremism, and accountability in intimate partner violence, leaving Rusk County forever scarred by the loss of an innocent life.

Final Appeals, Execution, and Lasting Echoes

For over a decade, Milam’s legal team mounted a series of appeals, each more desperate than the last, challenging the conviction on grounds of unreliable forensics and procedural errors. In 2019 and 2021, stays of execution were granted to review new evidence, including advancements in DNA analysis that questioned some trace matches. A pivotal argument centered on bite mark evidence, long criticized as pseudoscience.

A 2016 report from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology had deemed such analysis “clearly scientifically unreliable,” and Milam’s attorneys petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court in the days before his death, claiming it prejudiced the jury. They also argued the lack of a coherent motive undermined the case, suggesting the “exorcism” story was a fabrication to mask Carson’s sole culpability.

The Supreme Court denied the stay on September 25, 2025, paving the way for Milam’s transfer to the Huntsville Unit. Arriving anxious with a headache, he was placed in a holding cell near the death chamber, where chaplains offered spiritual counsel. At 6:19 p.m. CDT, the lethal injection of pentobarbital began flowing into his veins. Milam grunted once, gasped, then fell silent, snoring faintly before all movement ceased. He was pronounced dead at 6:40 p.m., just 18 minutes after Alabama executed another inmate, marking a grim doubleheader in American capital punishment.

In his final statement, delivered from the gurney with witnesses—including Amora’s family—arrayed behind glass, Milam showed no remorse for the crime but expressed gratitude and evangelism. “If any of you would like to see me again, I implore all of you no matter who you are to accept Jesus Christ as your Lord and Savior and we will meet again,” he said calmly. “I love you all. Bring me home, Jesus.” He thanked supporters and the prison’s faith-based programs for his religious awakening on death row, a transformation that humanized him in the eyes of some advocates but did little to console the victims’ loved ones.

The execution reignites debates over the death penalty’s efficacy and fairness, particularly in cases intertwined with mental health and junk science. Amora’s grandmother, speaking briefly to reporters outside the prison, called it “justice delayed but not denied,” while anti-death penalty groups decried it as state-sanctioned vengeance. As Texas continues its pace of executions—over 500 since 1982—this case stands as a cautionary tale of unchecked zealotry and the fragility of young lives. In the quiet trailers of Rusk County, the echoes of Amora’s cries may finally fade, but the questions they raise about faith, fury, and forgiveness endure.