Charon, Pluto’s largest moon, has long fascinated scientists with its mysterious icy surface and complex geological features. Using the cutting-edge capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), researchers have now detected carbon dioxide and hydrogen peroxide on Charon, offering fresh insights into this enigmatic moon and potentially other celestial objects in the Kuiper Belt region.

These findings mark a significant advancement in understanding Charon’s composition, providing clues about its origins and how the moon has evolved over billions of years.

The new discoveries, led by a team at the Southwest Research Institute (SWRI) in Boulder, Colorado, highlight the moon’s chemical diversity and hint at the evolutionary processes shaping it. Charon is the largest of Pluto’s five moons, measuring approximately 754 miles in diameter.

Read : North Korea Has Enough Uranium to Build Nuclear Weapons

What makes Charon particularly unique is its relationship with Pluto, which is often referred to as a double dwarf planet system due to the relative similarity in their sizes. Charon is about half the size of Pluto, an unusual relationship for a moon and its parent body.

Charon: A Window into the Early Solar System

Understanding Pluto’s largest moon surface and composition is a critical step in piecing together the broader mysteries of the outer solar system. The Kuiper Belt, where Pluto and Charon reside, is home to many icy bodies, dwarf planets, and comets.

Read : Hidden Ocean Discovered Beneath Pluto’s Icy Surface

By studying Charon, scientists can learn more about these other Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) that exist beyond Neptune’s orbit. These objects are considered time capsules, providing valuable information about the early days of our solar system.

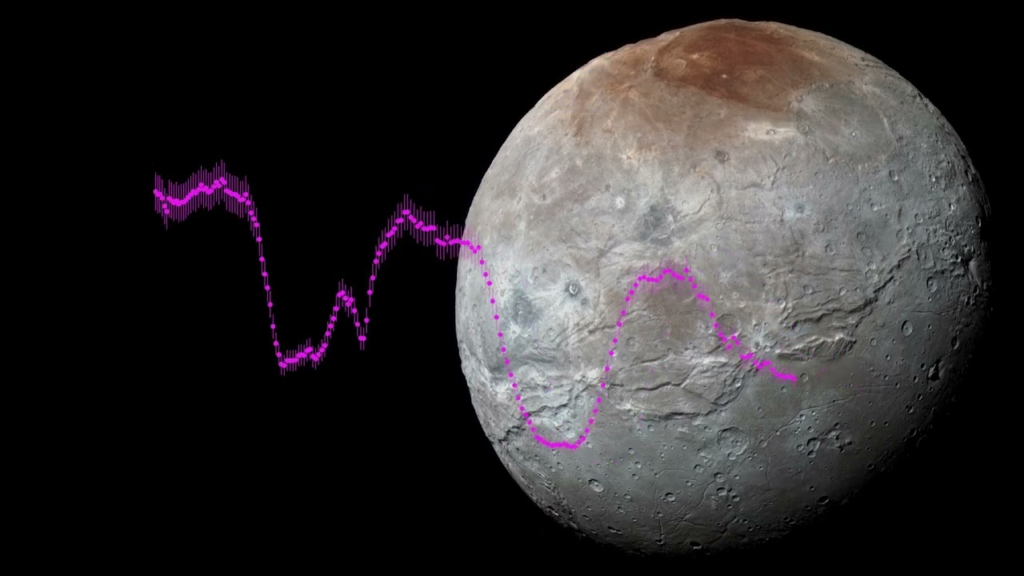

Charon has been a subject of interest since NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft provided the first detailed images of the moon in 2015. Those images revealed surprising features on Pluto’s largest moon surface, including a massive tectonic belt and a striking red region at its north pole.

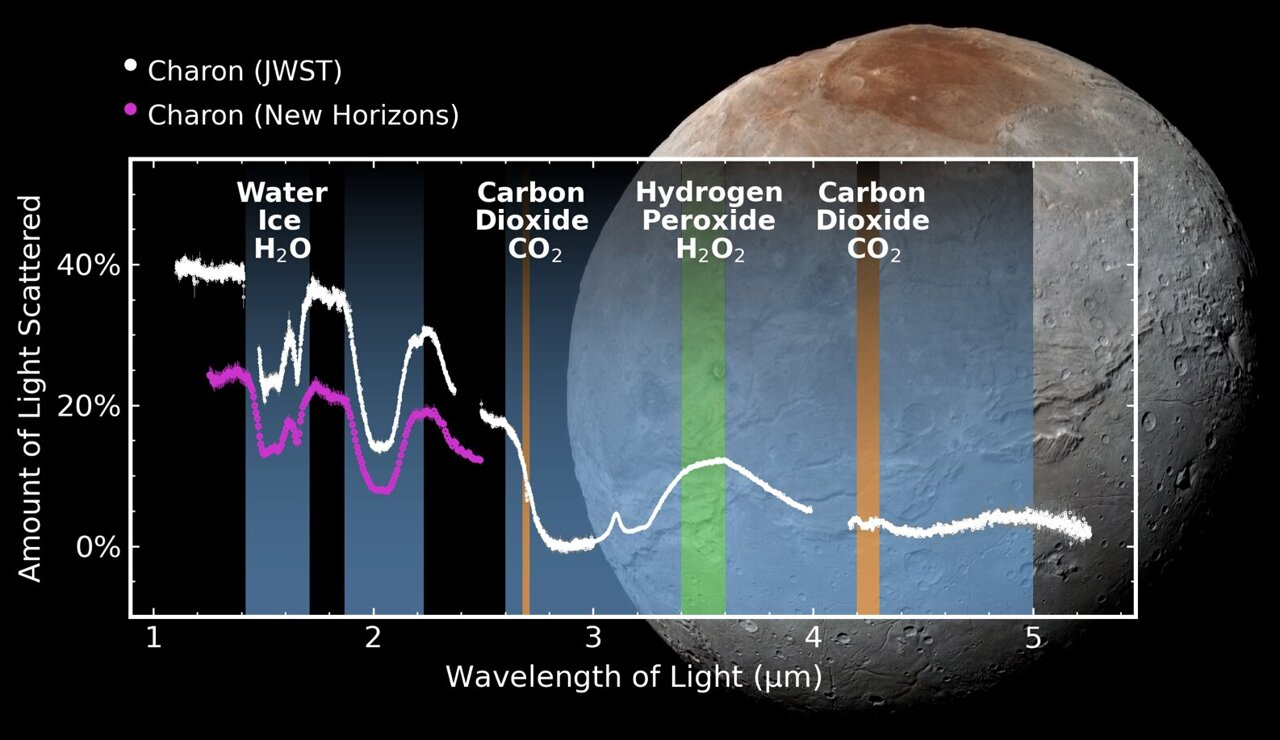

These features suggested that Pluto’s largest moon may have had a subsurface ocean of liquid water in the distant past. However, some critical details about Charon’s surface composition remained elusive. New Horizons, while groundbreaking, did not capture the full spectrum of light needed to reveal the moon’s complete chemical makeup.

With the JWST, astronomers now have the tools to delve deeper into Pluto’s largest moon secrets. The discovery of carbon dioxide and hydrogen peroxide adds a new layer of complexity to what was previously known about the moon’s surface.

Charon was already known to consist largely of crystalline water ice, ammonia, and organic compounds, but the presence of these additional elements suggests that Pluto’s largest moon has undergone more complex chemical processes than previously thought.

How Carbon Dioxide and Hydrogen Peroxide Formed on Charon

The detection of carbon dioxide and hydrogen peroxide on Pluto’s largest moon provides clues about how radiation from the Sun and other external forces have interacted with the moon’s surface over time.

As Pluto’s largest moon orbits Pluto in the distant reaches of the solar system, its surface is constantly bombarded by cosmic rays, solar radiation, and micrometeoroid impacts. These forces cause chemical reactions that can break down existing molecules and form new ones.

One hypothesis is that carbon dioxide on Pluto’s largest moon could be the result of radiation breaking down methane ice that might exist on the moon’s surface. Over time, exposure to cosmic rays could transform methane into more complex compounds, including carbon dioxide.

Similarly, hydrogen peroxide could form from water ice exposed to radiation, which splits the water molecules and allows them to bond into hydrogen peroxide.

These processes are not unique to Charon but are thought to occur across many icy bodies in the solar system, including other moons and TNOs. By studying how these compounds form and evolve, scientists can gain a better understanding of the history and dynamics of objects in the Kuiper Belt.

Implications for the Kuiper Belt and Beyond

The Kuiper Belt is a region that has remained relatively unexplored, but it holds great significance for understanding the formation of the solar system.

The objects within the Kuiper Belt are believed to be remnants of the primordial disk from which the planets formed over 4.5 billion years ago. As such, they offer a glimpse into the conditions that existed during the earliest stages of solar system development.

Charon’s chemical composition, now revealed in greater detail, could serve as a model for studying other objects in the Kuiper Belt. By comparing Charon’s surface with those of other TNOs, scientists can identify similarities and differences that may provide clues about the formation of these distant objects.

For instance, learning more about which compounds on Charon’s surface are pristine and which have been altered by external factors such as radiation can help scientists reconstruct the moon’s original state and, by extension, the state of other Kuiper Belt objects.

According to Silvia Protopapa, the lead researcher on the study, this distinction between pristine and altered materials is crucial. “Understanding this distinction is crucial for piecing together the nature of the primordial disk from which these objects formed 4.5 billion years ago,” she explains.

As more research is conducted, it will be important to determine how much of Charon’s surface has been modified by external forces and how much remains in its original state.

The ability to study Charon in such detail is a significant achievement for planetary science, and it underscores the capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope.

JWST’s advanced spectrographic instruments allow scientists to observe a wider range of light wavelengths than ever before, making it possible to detect compounds that were previously invisible to instruments like those on the New Horizons spacecraft.

The findings from Charon may also have broader implications for understanding the processes that shape icy bodies throughout the solar system.

Whether it’s studying the moons of the outer planets or investigating comets, learning how radiation, impacts, and other forces interact with these objects can provide valuable insights into the evolution of the solar system as a whole.

Charon’s Role in Future Exploration

As technology continues to advance, future missions may return to the Kuiper Belt to gather even more data on Charon and its neighboring objects. While the New Horizons mission provided a crucial first look, there is still much more to learn about this distant moon and its role in the broader context of the solar system.

Charon remains an exciting target for exploration because of its potential to reveal the history of not just Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, but also the early solar system.

The detection of carbon dioxide and hydrogen peroxide is just the beginning of what scientists hope will be a series of discoveries that unlock the mysteries of Charon and other TNOs. These findings will help refine our understanding of how these objects formed and evolved over billions of years.

As researchers continue to study Charon, they will likely uncover even more surprises about this distant moon. The continued exploration of Charon, aided by groundbreaking tools like the JWST, promises to reshape our understanding of the Kuiper Belt and the solar system’s outer reaches.

By studying Charon, scientists are not just learning about a single moon—they are unlocking the secrets of an entire region of space that holds the keys to understanding the solar system’s formation and evolution.