On August 29, 2025, the Utah Supreme Court made a significant ruling by halting the execution of Ralph Leroy Menzies, a 67-year-old death row inmate diagnosed with dementia. Menzies, convicted of the 1986 murder of Maurine Hunsaker, was scheduled to face execution by firing squad on September 5, 2025—a method he chose decades ago when given the option under Utah law.

The court’s decision came after Menzies’ legal team argued that his worsening dementia rendered him incompetent to face execution, citing both state and federal laws that require a defendant to have a rational understanding of their punishment. This ruling has reignited debates about the ethics of capital punishment, particularly for individuals with severe cognitive impairments, and has brought renewed attention to the prolonged suffering of the victim’s family.

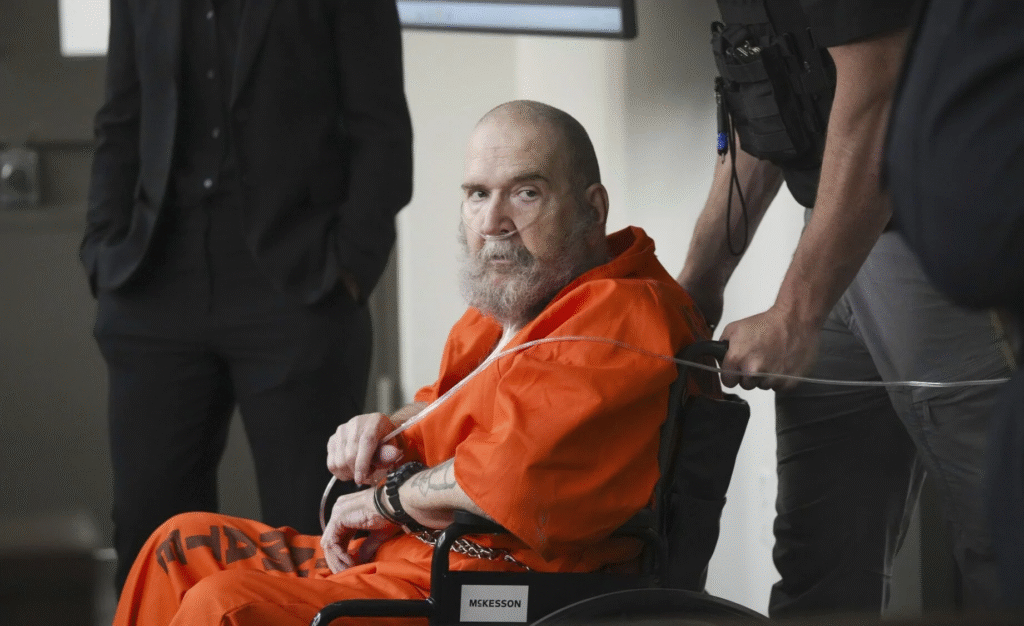

The case of Ralph Leroy Menzies is a complex intersection of legal, ethical, and medical considerations. Having spent 37 years on death row, Menzies’ health has deteriorated significantly, with his attorneys emphasizing that his vascular dementia has left him wheelchair-bound, oxygen-dependent, and unable to comprehend the reasons for his impending execution. The Utah Supreme Court’s decision to vacate his death warrant and order a reevaluation of his mental competency underscores the evolving legal standards surrounding capital punishment and mental illness.

The Utah Supreme Court’s Ruling and Legal Rationale

The Utah Supreme Court’s decision to block Menzies’ execution was grounded in the principle that executing a person who lacks the mental capacity to understand the reason for their punishment violates constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment. In an opinion authored by Chief Justice Matthew Durrant, the court determined that Menzies’ legal team had adequately demonstrated a “substantial change of circumstances” regarding his mental health since his last competency evaluation in 2024.

The court vacated the death warrant issued by Third District Court Judge Matthew Bates, who had previously ruled in June 2025 that Menzies was competent to be executed despite his dementia diagnosis. The court’s ruling hinged on the progression of Menzies’ vascular dementia, a condition that impairs cognitive function due to disrupted blood flow to the brain. Recent medical evaluations presented by the defense indicated that Menzies’ condition had worsened significantly, to the point where he no longer appeared to understand why he was facing execution.

Chief Justice Durrant emphasized that Judge Bates had erred by considering the state’s rebuttal evidence during the initial competency hearing, rather than focusing solely on whether the defense’s evidence warranted a new evaluation. The court ordered the case back to the Third District Court for an independent reevaluation of Menzies’ competency, effectively pausing the execution process.

Read : Iran’s Black Widow Faces Execution for Poisoning 11 Husbands to Death

The Utah Supreme Court acknowledged the emotional toll on Maurine Hunsaker’s family, stating, “We acknowledge that this uncertainty has caused the family of Maurine Hunsaker immense suffering, and it is not our desire to prolong that suffering. But we are bound by the rule of law.” This statement reflects the court’s attempt to balance the legal obligation to ensure a fair process with the undeniable pain experienced by the victim’s family, who have waited nearly four decades for closure.

Ralph Leroy Menzies who has been on death row for nearly 40 years has been declared competent to be put to death despite suffering from dementia. He was found guilty in the death of Maurine Hunsaker. pic.twitter.com/zjaWiP25f9

— Drilliam Shakespeare (@DrilliamS) June 11, 2025

The ruling aligns with U.S. Supreme Court precedents, notably the 2019 case of Vernon Madison, an Alabama death row inmate whose execution was blocked due to dementia. The U.S. Supreme Court has consistently held that executing someone who cannot rationally understand their punishment fails to serve the retributive purpose of the death penalty and violates the Eighth Amendment.

The Crime and Menzies’ Long Journey on Death Row

Ralph Leroy Menzies was convicted in 1988 for the brutal murder of Maurine Hunsaker, a 26-year-old mother of three, on February 23, 1986. Hunsaker was working at a convenience store in Kearns, a suburb of Salt Lake City, when Menzies abducted her. She managed to call her husband to report that she had been robbed and kidnapped but believed she would be released that night.

Tragically, her body was discovered two days later by a hiker in Big Cottonwood Canyon, approximately 16 miles away. Hunsaker had been strangled, her throat slashed, and she was tied to a tree. When Menzies was arrested on unrelated charges, authorities found Hunsaker’s wallet and other belongings in his possession, leading to his conviction for first-degree murder and other crimes.

At the time of his sentencing, Utah allowed death row inmates sentenced before May 2004 to choose between lethal injection and firing squad. Menzies, like others sentenced during that period, opted for the firing squad—a method that has been used sparingly in the United States, with only five executions by this means since 1977.

Utah’s last firing squad execution was in 2010, when Ronnie Lee Gardner was put to death. Menzies’ choice of execution method has drawn attention due to its rarity and the ethical questions surrounding its use, particularly in light of a recent South Carolina case where a firing squad execution resulted in prolonged suffering for the inmate.

Menzies has spent 37 years on death row, during which his health has deteriorated significantly. His attorneys argue that his vascular dementia, diagnosed after multiple falls in prison, has led to severe memory loss, cognitive decline, and physical frailty. An MRI exam revealed deteriorating brain tissue, and Menzies now relies on a wheelchair and oxygen support.

His legal team contends that his condition renders him no longer a threat to society and that executing him would serve no meaningful purpose. However, prosecutors have presented conflicting medical opinions, asserting that Menzies retains sufficient mental capacity to understand his situation, a claim that will now be reexamined in the lower court.

The prolonged duration of Menzies’ time on death row has also been a point of contention for Hunsaker’s family. Matt Hunsaker, Maurine’s son, who was 10 years old at the time of her murder, has expressed frustration at the decades-long delay in achieving justice.

Speaking at a hearing in July 2025, he told Judge Bates, “You issue the warrant today, you start a process for our family. It puts everybody on the clock. We’ve now introduced another generation of my mom, and we still don’t have justice served.” The family’s anguish underscores the emotional complexity of the case, as they grapple with the desire for closure against the legal system’s careful deliberation over Menzies’ mental state.

Broader Implications for Capital Punishment and Dementia

The Utah Supreme Court’s ruling in Menzies’ case raises critical questions about the application of the death penalty in cases involving severe mental illness or cognitive impairment. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2019 decision to block Vernon Madison’s execution set a precedent that defendants who cannot rationally understand their punishment are protected under the Eighth Amendment.

This principle stems from the idea that the death penalty’s primary purposes—retribution and deterrence—are undermined if the individual being executed cannot comprehend the connection between their crime and punishment. Menzies’ case tests the boundaries of this standard, as medical experts remain divided on his level of competency. The case also highlights the ethical challenges of executing individuals who develop debilitating conditions during lengthy periods on death row.

Menzies’ 37 years in prison are not unusual in the U.S. capital punishment system, where appeals and legal challenges often delay executions for decades. Critics argue that such prolonged incarceration, coupled with the onset of conditions like dementia, raises questions about whether the punishment remains just or humane. Menzies’ attorney, Lindsey Layer, articulated this sentiment, stating, “Taking the life of someone with a terminal illness who is no longer a threat to anyone and whose mind and identity have been overtaken by dementia serves neither justice nor human decency.”

Furthermore, the use of the firing squad as an execution method has drawn scrutiny in this case. While Menzies chose this method decades ago, recent executions by firing squad in South Carolina have raised concerns about their reliability and humaneness. In April 2025, South Carolina executed Mikal Mahdi by firing squad, and reports indicated that he remained conscious and in pain for up to a minute after the shots were fired, prompting renewed debate about the method’s cruelty.

Only four states—Utah, Idaho, Mississippi, and Oklahoma—currently allow firing squad executions, and Menzies’ case has brought attention to the practical and ethical implications of this choice. The Utah Supreme Court’s decision also reflects broader shifts in public and political attitudes toward the death penalty. While capital punishment remains legal in 27 states, its use has declined in recent years, with fewer executions carried out annually.

Former President Joe Biden imposed a moratorium on federal executions except in cases of terrorism and hate-motivated mass murder, while President Donald Trump, upon returning to office, prioritized restoring the death penalty’s use. These contrasting approaches highlight the polarized nature of the debate, with Menzies’ case serving as a microcosm of the tension between justice, mercy, and the rule of law.

The Utah Supreme Court’s decision to block Ralph Leroy Menzies’ execution on August 29, 2025, represents a pivotal moment in the ongoing debate over capital punishment and mental competency. By ordering a reevaluation of Menzies’ dementia and its impact on his ability to understand his punishment, the court has reaffirmed the importance of constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment. The ruling acknowledges the profound suffering of Maurine Hunsaker’s family, who have waited nearly four decades for justice, while also upholding the legal principle that executing an incompetent individual serves no societal purpose.

As the case returns to the Third District Court for further evaluation, it will likely continue to spark discussion about the ethics of the death penalty, the use of firing squads, and the treatment of inmates with severe cognitive impairments. Menzies’ fate remains uncertain, but the court’s decision underscores the judiciary’s role in navigating the complex interplay of law, morality, and human rights in the administration of justice.