The arrest of Pastor Ezra Jin Mingri, a leading figure in China’s Christian underground church movement, has sent shockwaves across both the Chinese and international Christian communities. As authorities intensify crackdowns on unregistered religious groups, Zion Church—one of the largest independent house churches in China—has once again become the center of government scrutiny. The detentions, involving Jin and dozens of pastors, staff, and members, mark a new chapter in the long struggle for religious freedom in China and highlight the ongoing tension between the Chinese Communist Party and faith communities operating outside state control.

A Sweeping Crackdown on Zion Church and Its Leaders

Pastor Ezra Jin Mingri, founder and spiritual leader of Zion Church, was arrested on Friday at his home in Beihai, Guangxi province, according to his daughter, Grace Jin Drexel. Drexel, who now lives in the United States, confirmed the arrest and described the ordeal as both terrifying and faith-testing for the family. “It’s been extremely shocking and very scary for our family,” she said, adding that they remain steadfast in their belief that Jin is continuing God’s work even amid persecution.

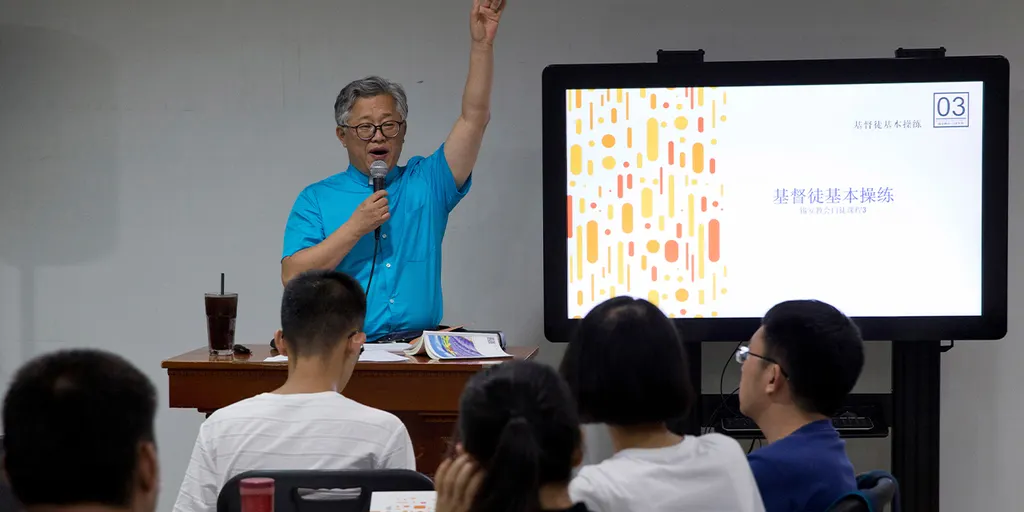

Zion Church, which operates outside the state-sanctioned Three-Self Patriotic Movement, is one of China’s most influential “house churches.” Founded in 2007, the church quickly expanded its reach through a network of local gatherings and digital platforms, attracting between 5,000 and 10,000 worshippers weekly. Despite this growth, its independence from state oversight has made it a frequent target of government suppression. In 2018, authorities forcibly shut down Zion Church’s main campus in Beijing, confiscating property and detaining several members. Yet the church persisted, reorganizing through smaller local fellowships and online services, symbolizing both the resilience and vulnerability of China’s unregistered Christian movement.

The recent arrests began on Thursday, when police launched coordinated operations across several provinces. Sean Long, a pastor and spokesperson for Zion Church, reported that more than 30 pastors and staff members were detained or became unreachable. Witnesses said that police officers carried “wanted lists” and, in some cases, used violence during the raids. One female pastor was reportedly separated from her newborn baby. Authorities have accused several church leaders of “illegally disseminating religious information online,” a charge commonly used to silence Christian figures who preach or share religious materials on digital platforms without state authorization.

According to Long, the sweep appears to have been premeditated and comprehensive, targeting Zion Church’s leadership structure and communication channels. “We strongly appeal to the global church society to hold the Chinese government accountable,” Long said. “They cannot do whatever they want without letting people know. Let our ministers and staff members be released as soon as possible. Stop arresting our members.”

Read : Church of England Faces Threat of Split Over Stance on Gay Couples

Photographs released by Long show Zion Church pastor Sun Cong standing handcuffed in his Beijing home, surrounded by police officers. The image, now circulating widely online, has become a stark symbol of the repression faced by Chinese Christians who refuse to submit their congregations to state control.

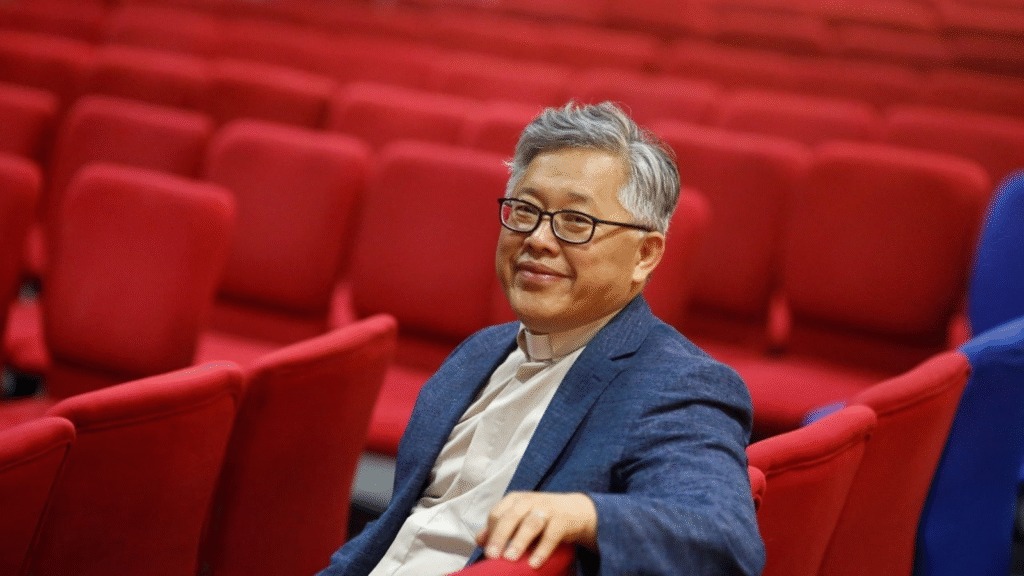

Faith, Conviction, and the Legacy of Pastor Ezra Jin

Pastor Ezra Jin is not an unfamiliar name in China’s religious landscape. Before becoming a pastor, Jin was a student at Peking University during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests—a time that profoundly shaped his understanding of authority, conscience, and faith. He later pursued theological training in the United States, earning a doctorate in ministry from Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. Despite opportunities to remain abroad, Jin chose to return to China to serve his congregation, fully aware of the risks involved in leading an unregistered church.

Jin’s daughter revealed that her father had recently expressed a strong sense of foreboding about possible imprisonment. In recent weeks, he had spoken to family and church colleagues about preparing for persecution and leaving behind a record of his ministry for his grandchildren. “He was very clear-eyed about what the government is and what he is doing,” Drexel said. “He became a pastor knowing that one day it is possible that he will be imprisoned.”

His decision to return to China after the 2018 crackdown, rather than seek asylum in the U.S., reflected his unwavering commitment to his congregation. “He felt that he had to go back with the church and be with the church while it was suffering,” his daughter said.

Ezra Jin’s leadership style has long combined theological depth with civic courage. Under his guidance, Zion Church became known for its intellectual engagement and social outreach, appealing particularly to young urban professionals seeking meaning beyond material success. The church’s model—modern, educated, and digitally connected—challenged the state’s perception of Christianity as a marginal or foreign faith.

In the eyes of many Chinese Christians, Jin embodies a new generation of spiritual leaders who represent both religious revival and civil conscience. His arrest, therefore, is not only a personal tragedy but also a symbolic assault on a movement that has quietly grown into one of the most significant grassroots faith communities in contemporary China.

Despite the detentions, Zion Church leaders have vowed to continue their ministry through online services and underground gatherings. “We will still have online service and we will not stop what we are doing,” Long said. “We will share the good news of Jesus Christ no matter what.” This persistence reflects the enduring spirit of China’s house churches, which, despite decades of state repression, continue to thrive in private homes, rented spaces, and encrypted digital platforms.

International Response and the Politics of Religious Freedom

The arrest of Pastor Jin and dozens of Zion Church members has sparked immediate international condemnation. U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued a statement calling for the immediate release of the detained pastors and church workers, describing the crackdown as evidence of the Chinese Communist Party’s hostility toward unregistered Christian groups. “This crackdown further demonstrates how the CCP exercises hostility towards Christians who reject Party interference in their faith and choose to worship at unregistered house churches,” Rubio said.

The incident also comes amid escalating tensions between Washington and Beijing, particularly regarding trade and human rights. Just a day before the arrests, U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to impose a 100% tariff on Chinese imports, intensifying an already fraught relationship between the two powers. Analysts suggest that the timing may not be coincidental, as Beijing often tightens internal controls on perceived sources of foreign influence during periods of geopolitical confrontation.

China’s Foreign Ministry has denied knowledge of the arrests. Spokesman Lin Jian told NPR that “the Chinese government manages religious affairs in accordance with the law, protects citizens’ freedom of religious belief and normal religious activities.” Lin also criticized what he described as U.S. interference in China’s internal affairs “under the pretext of so-called religious issues.”

The Chinese government officially recognizes five religions—Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism—but requires all religious organizations to register under state-controlled bodies. Independent churches like Zion, which operate outside these frameworks, are considered illegal and often face harassment, raids, and detention of their leaders. The government’s underlying concern, analysts argue, is not merely theological but political: the existence of large, organized groups loyal to authorities other than the Party is viewed as a potential challenge to social control.

This suspicion has extended beyond Christianity. In recent years, the government has detained Uyghur Muslims in reeducation camps in Xinjiang and restricted religious education, fasting, and dress. Both Islam and Christianity are often viewed by Chinese officials as “foreign religions” susceptible to Western influence. Nonetheless, tens of millions of Chinese citizens continue to practice Christianity in unregistered congregations, many of which rely on digital networks and personal relationships to sustain their faith.

Zion Church’s rapid growth, combined with its intellectual leadership and limited transparency, may have triggered official alarm. Pastor Long suggested that the authorities’ actions stem from both fear and misunderstanding. “We are not criminals but Christians,” he said. “We are not anti-CCP, we are not anti-China. We love our people, love our society, love our culture. We are not a Western political force. That is 100% wrong. We are a Chinese house church adhering to historic Christian faith. We are believers of Jesus. We have nothing to do with the U.S.-China tension or competition.”

The statement underscores an enduring paradox: while the Chinese government frames such crackdowns as legal enforcement or counter-foreign measures, the affected communities insist that their mission is purely spiritual, not political. For many observers, the persecution of Zion Church reveals the fragility of religious freedom in China’s modern state apparatus—one that allows worship only under total supervision.

Within China, fear now grips many Zion Church members, who face uncertain futures as they attempt to continue worship under surveillance and intimidation. Yet, there is also a sense of spiritual defiance. For believers, the suffering of their leaders affirms their conviction that faith cannot be extinguished by force. Grace Jin Drexel echoed this belief, saying her father’s imprisonment will not silence the gospel he preached. “We have faith in the Lord,” she said. “We know that he is doing God’s work.”

The detentions of Pastor Ezra Jin and his colleagues highlight an enduring truth about China’s religious landscape: faith continues to thrive even under pressure, adapting to new forms of worship, communication, and community. As international concern grows and diplomatic tensions rise, the fate of Zion Church may once again serve as a test of Beijing’s willingness to tolerate independent expressions of belief—and of the world’s readiness to defend them.

I really like your writing style, fantastic info, regards for posting :D. “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.” by T. S. Eliot.

I conceive this website holds some rattling excellent info for everyone :D. “The public will believe anything, so long as it is not founded on truth.” by Edith Sitwell.

Admiring the dedication you put into your site and in depth information you provide. It’s great to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same outdated rehashed material. Excellent read! I’ve bookmarked your site and I’m adding your RSS feeds to my Google account.