In a momentous development for human rights advocates worldwide, Egyptian-British activist Alaa Abd El-Fattah walked free from prison on September 23, 2025, following a presidential pardon issued by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Abd El-Fattah, a symbol of resistance against authoritarianism, had endured nearly 12 years of intermittent detention over the past decade, much of it under harsh conditions that drew global condemnation. His release marks a rare victory in Egypt’s ongoing crackdown on dissent, where thousands of political prisoners remain behind bars.

This event not only reunites a family torn apart by prolonged separation but also reignites hope for broader reforms in a nation still grappling with the legacy of the Arab Spring. The pardon, announced on September 22, 2025, came after years of tireless campaigning by Abd El-Fattah’s family, international diplomats, and human rights organizations. State media, including Al Ahram and al-Qahera News, confirmed that the decree annuls the remainder of his sentence, allowing for immediate release upon publication in the official gazette.

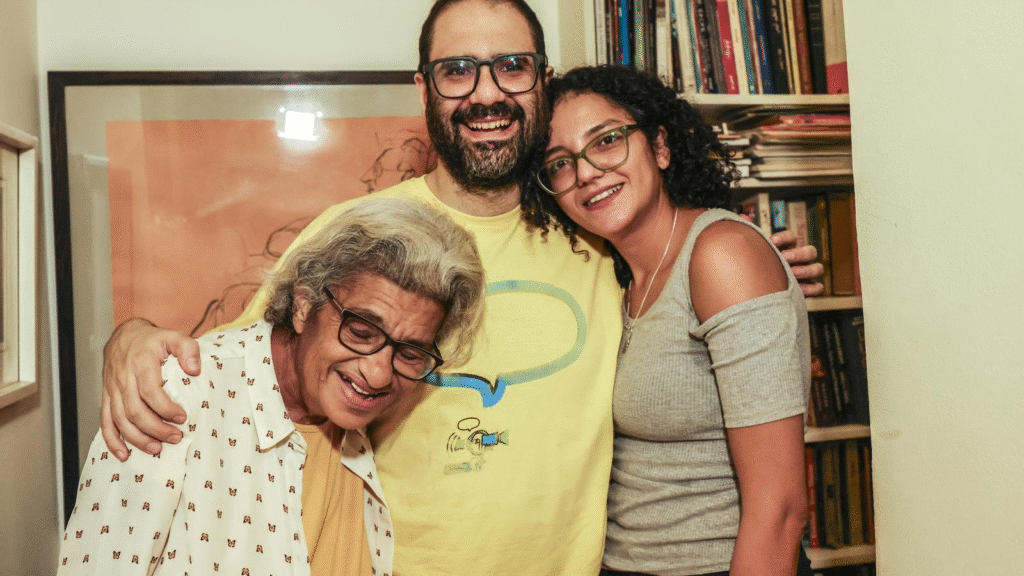

Abd El-Fattah’s case had become emblematic of Egypt’s stifled democracy, where even sharing a Facebook post could lead to years of incarceration. As crowds gathered outside Wadi al-Natroun prison, about 100 kilometers northwest of Cairo, the air was thick with anticipation. When the gates finally opened, the activist emerged to tearful embraces from his mother, Laila Soueif, and sisters, Sanaa and Mona Seif, in a scene captured in widely shared family photos showing unbridled joy amid exhaustion.

This release arrives at a pivotal time for Egypt, as the country navigates economic pressures and international scrutiny ahead of future global events. While the pardon extends to five other prisoners, Abd El-Fattah’s prominence amplifies its significance. British Foreign Secretary Yvette Cooper hailed the news, stating it allows him to return to the UK and reunite with his young son, who has been studying abroad.

Pro-democracy Egyptian-British activist Alaa Abd el-Fattah has reunited with family after his prison release.

— Sky News (@SkyNews) September 23, 2025

El-Fattah was one of the most prominent Egyptian activists in the 2011 Arab Spring uprising. He was released from prison after being granted a presidential pardon. pic.twitter.com/zbZemoD1AF

Human Rights Watch researcher Amir Magdi echoed this sentiment but tempered celebrations, noting that over 60,000 political detainees still languish in Egyptian prisons. For many, this moment underscores the power of persistent advocacy, yet it serves as a stark reminder of the unfinished struggle for freedom in the Arab world’s most populous nation.

Alaa Abd El-Fattah: A Legacy of Defiance and Digital Activism

Alaa Abd El-Fattah, born in 1982 to a family of intellectuals and activists, has long been a thorn in the side of Egypt’s ruling elite. A software developer by training, he rose to prominence during the 2011 Tahrir Square uprising that toppled longtime dictator Hosni Mubarak. At just 28, Abd El-Fattah was at the forefront, using his tech savvy to organize protests via social media and coordinate logistics for demonstrators. His blog, “Man in Blue,” became a chronicle of the revolution, blending sharp wit with incisive analysis of power structures.

To a generation of young Egyptians, he was simply “Alaa”—an icon of the digital age who proved that keyboards could topple regimes as effectively as cobblestones. His activism, however, came at a steep personal cost. In the chaotic aftermath of Mubarak’s fall, Abd El-Fattah was briefly detained by the military in 2011 for allegedly inciting violence during a Coptic Christian protest.

Undeterred, he continued his work, co-founding the No Military Trials for Civilians campaign, which demanded accountability for the interim government’s abuses. By 2013, as the Muslim Brotherhood-led government under Mohamed Morsi faltered, Abd El-Fattah warned against the military’s return to power. When General el-Sisi orchestrated a coup that July, the activist’s criticisms turned prophetic. Labeled a “terrorist sympathizer,” he was arrested in late 2013 and sentenced to five years in 2014 for protesting without permission—a charge that masked deeper political retribution.

Upon his 2019 release, Abd El-Fattah wasted no time resuming his advocacy. He penned essays from hiding, critiquing Egypt’s surveillance state and the erosion of civil liberties. But freedom was fleeting; just six months later, in 2020, he was rearrested alongside lawyer Mohamed al-Baqer during a police raid on a rights group office.

This time, authorities accused him of “spreading false news” for sharing a Facebook post about a security forces killing of an unarmed man. The trial was a farce, riddled with due process violations: lawyers were denied access to evidence, and the five-year sentence handed down in 2023 was non-appealable. Even after serving the full term in 2024, he remained detained arbitrarily, his name lingering on a “terrorism” list until its removal earlier this year.

Abd El-Fattah’s writings from prison reveal a man unbroken by isolation. In letters smuggled out, he reflected on resilience, urging supporters not to despair. “Unlike me, you have not yet been defeated,” he wrote to a human rights conference, encapsulating his philosophy of sustained resistance. His dual British-Egyptian citizenship, acquired through his mother in 2021, amplified global attention, turning his plight into a diplomatic flashpoint. Yet, it was his unyielding voice—amplified through family and allies—that kept the flame of dissent alive.

The Road to Pardon: Family Struggles and Global Campaigns

The path to Abd El-Fattah’s freedom was paved with unyielding family resolve and relentless international pressure. His mother, Laila Soueif, a renowned mathematician and activist, became the face of the fight. In a desperate bid last year, the 70-year-old embarked on a 10-month hunger strike, subsisting on minimal calories to protest her son’s indefinite detention. Joined by Abd El-Fattah himself in sporadic fasts, their actions spotlighted the human toll of Egypt’s prisons. “We are not asking for mercy; we demand justice,” Soueif declared during a rare public appearance, her frail frame belying her fierce determination.

Sisters Sanaa and Mona Seif, both seasoned activists, orchestrated campaigns that bridged Cairo’s streets and London’s corridors of power. Sanaa, a filmmaker who endured her own imprisonment in 2014, lobbied UK officials relentlessly. In early 2025, she and Soueif met Prime Minister Keir Starmer, presenting evidence of procedural violations in Abd El-Fattah’s case. Mona’s social media updates—raw, real-time dispatches from prison vigils—garnered millions of views, fostering a global network of solidarity. “Alaa is free,” Mona posted triumphantly on September 23, alongside a photo of the family embrace, capturing the raw emotion of the moment.

International efforts peaked during high-profile events. At the 2022 COP27 summit in Sharm El-Sheikh, activists projected Abd El-Fattah’s image on walls, demanding his release amid Egypt’s hosting duties. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch documented his solitary confinement and health deterioration, pressuring Western governments to tie aid to prisoner releases.

Peter Greste, the Australian journalist jailed with him in 2013, celebrated the pardon as “vindication” for years of advocacy. Domestically, Egypt’s National Council for Human Rights—a state body—submitted an appeal in September 2025, citing “swift justice” reforms, which el-Sisi approved. Though critics view this as a gesture to appease abroad, it undeniably culminated in the decree that set Abd El-Fattah free.

Reactions and the Shadow of Broader Repression

News of the release triggered an outpouring of relief and cautious optimism. Family members, long shadows under surveillance, shared videos of Abd El-Fattah dancing in jubilation before hugging his mother, his yellow T-shirt a stark contrast to prison grays. “Despite our great joy, the biggest joy is when there are no political prisoners,” Soueif told reporters, her words a poignant call for systemic change. Sanaa echoed this, praying for an end to her family’s “tragedies” and freedom for Abd El-Fattah to join his son in the UK.

Globally, reactions blended elation with sobriety. UK officials expressed eagerness for his return, while Egyptian state media framed the pardon as humanitarian progress. Yet, activists like those at Peoples Dispatch warn that this is no panacea; el-Sisi’s regime has jailed dissidents en masse since 2013, with torture reports rampant. Abd El-Fattah’s freedom, they argue, should catalyze demands for the 60,000 others still held without fair trials.

Looking ahead, Abd El-Fattah’s voice—silenced for so long—could reshape narratives on Egyptian rights. Will he pen a memoir from exile? Rally anew from London? His release is a beacon, but as he himself might say, the real work begins now. In a world weary of authoritarian overreach, Alaa Abd El-Fattah reminds us that one person’s liberty can inspire a thousand more fights.