In a feat that blends innovation, efficiency, and environmental foresight, Japan has stunned the world once again by unveiling the First 3D-Printed Railway Station.

Located in the tranquil town of Arida, south of Osaka, this unassuming structure is nothing short of a technological marvel. Built in just six hours, the railway station stands as a symbol of Japan’s unwavering commitment to innovation and adaptability in the face of societal and infrastructural challenges.

At a time when many nations are still exploring the potential of 3D-printing for housing and urban solutions, Japan has taken the bold step of implementing this technology into its public transportation infrastructure. While the new station may appear modest in size, its implications for the future of construction, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability are enormous.

First 3D-Printed Railway Station

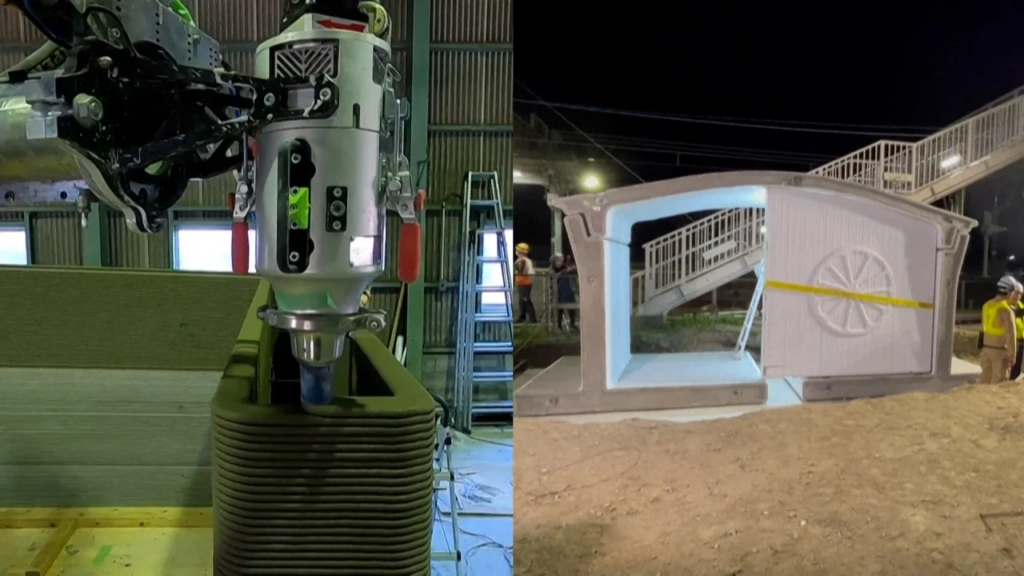

The station, now installed at Hatsushima on the Kisei Line, may resemble a quaint garden shed, but it is the culmination of cutting-edge 3D printing and traditional construction materials. Standing at 2.6 meters tall and covering an area of 100 square feet, it was constructed from reinforced concrete using mortar molds that were printed and pre-prepared off-site.

These molds were then trucked in and assembled overnight with the help of cranes, timed precisely between the last Monday night train and the first train on Tuesday morning. The efficient timing and execution meant that there was no disruption to train services or local commuter routines.

The construction project was spearheaded by the West Japan Railway Company (JR West) in collaboration with Serendix, a Japanese housing company that specializes in modular and 3D-printed structures.

Together, they aimed to demonstrate the potential of technology to address the growing challenges posed by Japan’s declining population and aging workforce—issues that particularly affect rural areas like Arida.

By shifting from traditional construction to 3D printing, JR West managed to cut down the estimated building time from two months to just six hours. This leap not only reduced labor costs and material waste but also halved the overall cost of the project.

How Japan Built a 3D-Printed Train Station

— Spiros Margaris (@SpirosMargaris) April 8, 2025

in 6 Hours https://t.co/BIpSqp2eaW @nytimes pic.twitter.com/aVauplnIjp

The design, although minimal, features subtle local touches, such as artistic representations of mandarin oranges and scabbardfish—both specialties of the Arida region—giving it a unique identity.

Preserving the Past While Building the Future

For residents of Arida, the replacement of the 75-year-old wooden station was both a cause for nostalgia and a source of local pride. Hatsushima Station, first built in 1938 and electrified in 1978, has long served as a link for the local community, providing access to the wider region and serving as a symbolic gateway to the nearby Jinoshima island, a popular spot for swimming and camping.

One of the local residents, 56-year-old Toshifumi Norimatsu, expressed mixed emotions as he watched the old structure being taken down to make way for the new. “I’m a little sad about the old station being taken down,” he told reporters. “But I would be happy if this station could become a pioneer and benefit other stations.”

Norimatsu’s words capture the duality of progress: while the old station stood as a testament to decades of rural life and simple, utilitarian architecture, the new 3D-printed version speaks of a future where even the smallest communities are not left behind in the march toward technological advancement.

JR West emphasized that despite its compact size, the new building meets modern standards. It is made of reinforced concrete, similar to residential housing, and is built to withstand earthquakes—no small concern in a country as seismically active as Japan. The building consists of four parts: the walls, roof, and two ends, which are pieced together with seamless precision.

While the exterior is complete, the station’s interior—such as ticket machines and IC card readers—is still being fitted. JR West plans to fully open the station to the public by July 2025. Once fully functional, the new structure will replace the wooden building that has served the town for three-quarters of a century.

Implications for the Future of Rural Japan

The decision to use 3D-printing technology for a rural train station is not merely an experiment—it’s a glimpse into a larger strategy. Japan, like many other advanced economies, is grappling with an aging population, labor shortages, and a need to upgrade aging infrastructure while keeping costs under control.

These challenges are particularly acute in rural areas, where populations are declining and investment returns are minimal. Traditional construction, with its higher labor and time costs, is increasingly seen as unsustainable for such regions.

By embracing modular, 3D-printed architecture, Japan is exploring new ways to make rural infrastructure more viable. The implications stretch far beyond train stations. If proven successful, similar approaches could be applied to other types of public buildings such as schools, medical clinics, and municipal offices.

Fast and cost-effective construction methods like this could reinvigorate declining communities, making them more accessible and better connected without requiring massive investment.

This initiative also reflects a broader global trend of using advanced technologies to reduce carbon footprints and construction waste. 3D printing uses materials more efficiently, allows for on-demand production, and reduces the need for excessive labor—all of which are crucial in a world increasingly conscious of climate impact and sustainability.

Furthermore, Japan’s achievement could serve as a model for other nations facing similar demographic and economic pressures. Countries with remote or underserved regions—where building infrastructure from scratch is often deemed too costly—might find in this case study a blueprint for innovation that is both practical and scalable.

In the case of Hatsushima Station, the technological feat is not merely in the speed of construction, but in what it symbolizes. It’s a commitment to progress without forsaking heritage, a balancing act between innovation and community identity. It respects the past by incorporating local motifs while signaling a bold step into the future.

As rural areas continue to decline in population, investments like these are essential not just for logistics, but also for morale. They demonstrate that innovation is not reserved for bustling urban centers or high-speed rail terminals—it can, and should, reach the heartlands too.

In a world still navigating how to make technology serve the public good without eroding tradition, Japan’s first 3D-printed railway station is a masterstroke. It tells a story of efficiency without coldness, modernization without alienation, and above all, a belief that every part of a country—no matter how small or quiet—deserves to be part of its future.