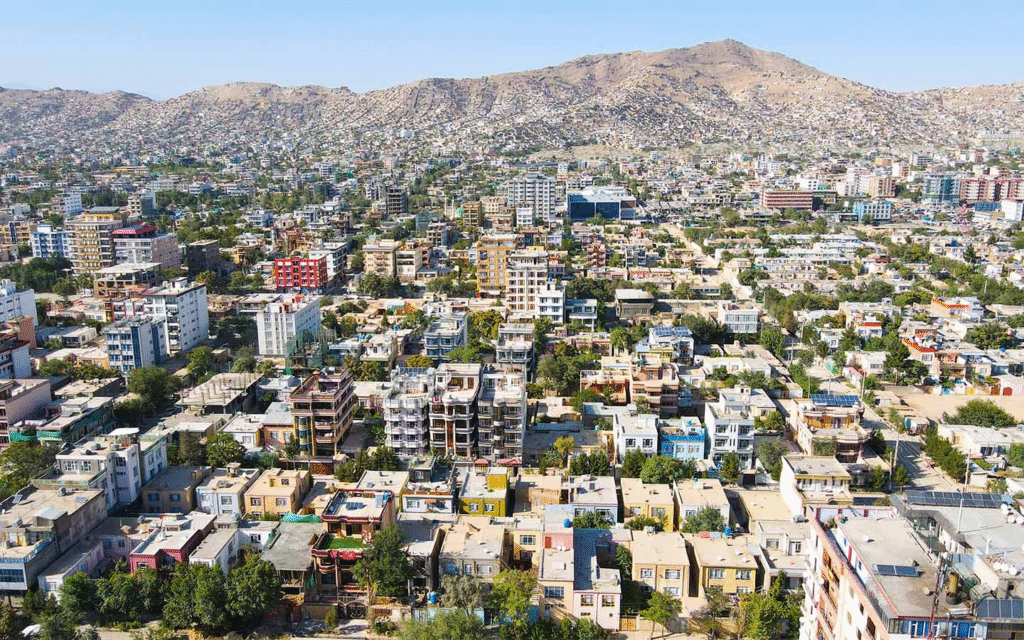

The capital of Afghanistan, Kabul, faces a looming and unprecedented crisis that threatens the survival of its over seven million inhabitants. Experts warn that Kabul may soon become the first modern city in the world to completely run out of water.

This alarming prospect is driven by a lethal combination of rapid urbanisation, climate change, weak governance, and international neglect. A recent report by the global humanitarian organisation Mercy Corps paints a bleak picture of Kabul’s water future, projecting that the city’s aquifers—its primary source of water—could dry up by as early as 2030.

This looming water catastrophe is more than a technical or environmental issue. It’s a human crisis that could destabilise communities, drive mass migration, and spark greater regional insecurity. As water becomes scarcer, the battle to access it is deepening poverty and hardship across Kabul, especially among its poorest residents.

What was once a natural resource available to all is quickly becoming a commodity only the wealthy can afford. Yet amidst the chaos and fear, many locals remain hopeful that with immediate action, change is still possible.

A Drying City: The Collapse of Kabul’s Aquifers

Over the last decade, Kabul’s aquifers have dropped by as much as 30 metres. These underground reservoirs were once the lifeline of the city, providing drinking water to millions through boreholes and wells. But today, nearly half of these boreholes have run dry, and water extraction is outpacing the natural recharge rate by an alarming 44 million cubic metres each year.

The unchecked urban sprawl of Kabul—whose population has grown sevenfold since 2001—has placed enormous pressure on the city’s limited water resources. Entire neighbourhoods that once depended on shallow wells are now forced to dig deeper or pay exorbitant prices to private vendors.

Read : Taliban’s Refugee Minister Killed in a Suicide Bombing by ISIS in Kabul

Climate change only worsens the situation by reducing snowfall and rainfall, both crucial to replenishing groundwater. The result is a collapsing water system that experts say could disappear entirely by the end of this decade.

Read : Environmental Alarms: Uncovering the Top 10 Most Polluted Nations

The lack of long-term planning and sustainable infrastructure has exacerbated the water crisis. Without effective regulation or oversight, private companies continue to dig new wells, draining shared resources for profit. The government, grappling with political instability and global isolation, has done little to halt the extraction or invest in lasting solutions. For the people of Kabul, every drop of water has become a struggle.

The Human Cost: Daily Battles and Rising Desperation

The effects of the water crisis are being felt in every home and on every street of Kabul. Many families now spend up to 30% of their monthly income just to access water. For the city’s poor, this means making heartbreaking choices between food, medicine, or clean water. Over two-thirds of households have incurred water-related debt, and contamination has become another deadly threat. Up to 80% of Kabul’s groundwater is unsafe due to high levels of sewage, arsenic, and salinity.

Nazifa, a teacher in the Khair Khana neighbourhood, captures the daily anguish of Kabul’s residents: “Every household is facing difficulty, especially those with low income. Adequate, good quality well water just doesn’t exist.” Her story is echoed by millions who must now queue for hours, pay double the price they paid just a year ago, or ration water in ways that affect hygiene, health, and dignity.

Private water tankers, once seen as a temporary fix, are now a booming industry. Companies extract groundwater from the remaining viable wells and sell it at inflated prices. What was once a communal good is now being monopolised, deepening inequality. “We used to pay 500 afghanis every 10 days to fill our cans,” says Nazifa. “Now, that same amount of water costs us 1,000 afghanis.” For many, these prices are simply unaffordable.

Women and children are often the most affected. As traditional water collectors in Afghan households, their burden has increased manifold. Instead of attending school or pursuing work, many spend their days fetching water or negotiating with vendors. In some areas, tensions have turned into open conflict as neighbours argue over access to community wells or tankers.

The Path Ahead: Solutions, Obstacles, and Global Neglect

Despite the bleak outlook, experts and citizens alike believe that solutions are still possible—but only if immediate and coordinated efforts are made. Mercy Corps Afghanistan country director Dayne Curry stresses the urgency: “No water means people leave their communities. For the international community to not address the water needs of Afghanistan will only result in more migration and more hardship.”

One promising initiative is the Panjshir River pipeline, a project designed to deliver potable water to 2 million people in Kabul. The design phase was completed in late 2024, but budget approval remains stalled. The estimated cost of $170 million has so far deterred swift progress, and the Afghan government is seeking outside investors to make up the shortfall.

Yet with time running out, delays could spell disaster. “We don’t have time to sit around waiting for budgets,” warns Dr Najibullah Sadid, a senior researcher on water resource management. “Whichever project will bring the most immediate impact is the priority. We just need to start somewhere.”

Meanwhile, international aid efforts are failing to keep pace with the crisis. In early 2025, the UN’s humanitarian office reported that only $8.4 million of the required $264 million in water and sanitation funding had been secured. Furthermore, around $3 billion in international funding remains frozen due to the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021. The U.S. decision to cut more than 80% of its USAID funding has only deepened the crisis.

For many in Kabul, this political paralysis feels like betrayal. “Water is a human right and a natural resource of Afghanistan. It is not a political issue,” says Nazifa. “My heart bleeds when I look at the flowers and fruit trees in the garden, all drying up. But what can we do? We are currently living in a military state, so we can’t exactly go to the government to report the issue.”

Experts argue that foreign governments must shift focus from short-term fixes to long-term, sustainable infrastructure. Digging a few more wells or delivering bottled water can’t replace a functioning water management system. There needs to be significant investment in rainwater harvesting, surface water management, and restoring natural recharge areas.

The Afghan Water and Environment Professionals Network has called for greater documentation of the crisis and stronger engagement with both local and international stakeholders. Yet until the political will aligns with the technical needs, the clock continues to tick.

A City on the Brink

Kabul’s water crisis is a stark reminder of the vulnerabilities modern cities face in an age of climate disruption and geopolitical instability. With every passing year, the possibility that Kabul will be the first modern city to run out of water becomes more real. Yet this crisis also presents an opportunity—to learn, to act, and to invest in systems that can protect not just Kabul, but other water-stressed cities across the globe.

The people of Kabul are not passive victims. They are investing what little they have into survival and sustainability. But they cannot do it alone. The world must take notice, not just with words, but with resources, action, and urgency. Because when a city runs out of water, it’s not just a local tragedy—it’s a global failure.