Qing Chenjingliang’s story is one of twists, contradictions, and public fascination. Once an obscure young woman from Mianyang in Sichuan province, Qing shot to national attention in 2018—not for any noble achievement, but for being part of a fraud ring that deceived victims through manipulation and threats.

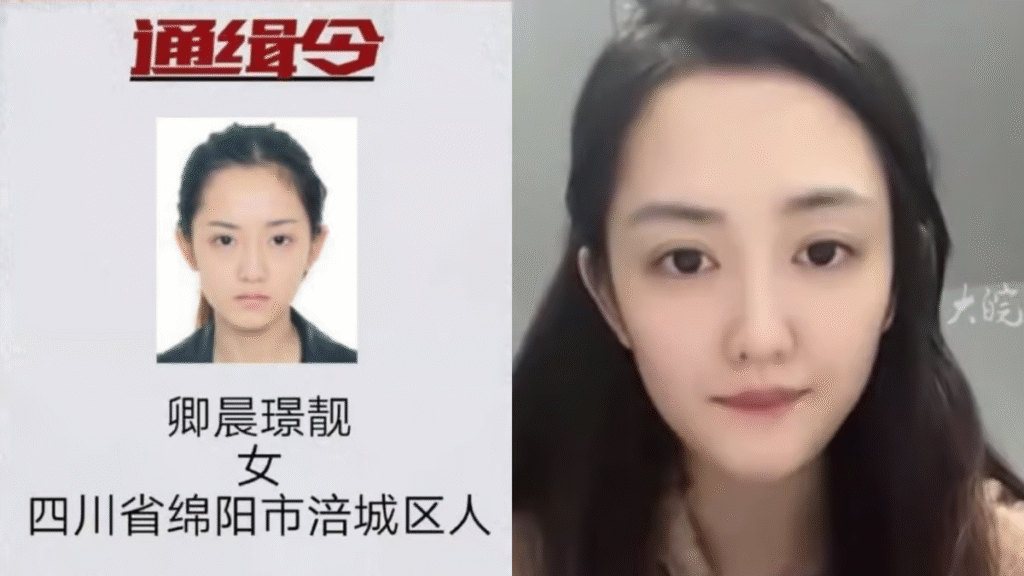

Her arrest warrant photo went viral across China, earning her the nickname “China’s most beautiful fugitive” and cementing her image in the public psyche. After turning herself in, Qing served a prison sentence of one year and two months for her role in a 10-person scam operation that cheated victims out of over 1.4 million yuan.

During her incarceration, she underwent ideological reeducation, legal studies, and labor reform—China’s traditional correctional method aimed at rehabilitation. By November 2021, she had completed her sentence and was released from prison, determined to begin a new chapter.

Her decision to re-enter society with a focus on redemption and education seemed noble to many. She opened a bubble tea shop and even appeared in a police-produced anti-fraud video, which drew both praise and backlash.

While some applauded her willingness to use her criminal past as a cautionary tale, others criticized the move, accusing authorities of glamorizing crime and creating the dangerous illusion that beauty and notoriety could lead to fame and opportunity.

From Fugitive to Educator: Qing’s Social Media Revival

Determined to show the world she had turned over a new leaf, Qing Chenjingliang launched a social media account in March under her full name. With her infamous 2018 wanted poster photo as her profile image, she began a twice-daily livestreaming routine in which she shared legal knowledge, personal insights, and detailed accounts of how she became involved in a fraudulent network.

Her bio openly acknowledged her past: “I was a headline figure in 2018 news. Now I have turned over a new leaf.” In her livestreams, she offered valuable advice on how to identify and avoid common scams, particularly those like the ones she had once participated in—elaborate social traps conducted under the guise of flirtation or friendly banter, often leading victims to bars where they were coerced into spending huge sums of money.

Read : China’s Bizarre Attempt to Resemble Mount Fuji in Universe Fantasy Land Faces Backlash

“Do not believe in something for nothing,” she warned in one of her videos, calling out the psychology behind bar scams and false online connections.

Read : China’s Chang’e 6 Spacecraft Successfully Returns with Samples from Far Side of Moon

While she frequently reminded viewers of her past title as the “most beautiful fugitive,” she was also careful to stress that she had served her time and was not glamorizing her crimes. Instead, she framed her experience as a way to educate the public. “Getting a sentence reduction is very difficult,” she said in one of her streams, attempting to dispel the notion that her looks or popularity led to special treatment.

However, her increasing popularity—nearly 10,000 followers in a short span—and her willingness to accept virtual gifts in exchange for deeper insights into her prison experience and criminal background began to stir public and regulatory concern. While Qing maintained that her intent was educational and reformative, others accused her of capitalizing on infamy and sensationalism.

Public Reaction and Social Media Backlash

On April 27, Qing’s social media presence came to a sudden halt. Her account was banned, all her videos were wiped, and her profile became unsearchable. The platform later released a statement clarifying that content exploiting criminal history for attention or profit violated community standards and policies. This sparked another wave of intense public debate online, with reactions sharply divided.

On one hand, many netizens defended Qing, arguing that she had served her sentence and had the right to rebuild her life in any legal way she saw fit—including becoming a livestreamer. “A prodigal who returns is more precious than gold,” one commenter wrote, echoing a Chinese proverb that stresses the value of redemption.

Supporters viewed her livestreams as a rare example of a former convict using firsthand knowledge to make a positive impact on society by preventing others from falling victim to similar schemes.

Others, however, were far more critical. Detractors argued that Qing’s choice to use her criminal identity—and specifically the nickname “most beautiful fugitive”—as a marketing tool was morally questionable.

“She takes pride in being the ‘most beautiful fugitive’. This mindset is deeply distorted,” one user noted. Critics claimed that the promotion of such a figure, even under the banner of education, risked sending a harmful message to impressionable viewers: that crime and infamy could lead to fame and income.

There was also concern about the commercialization of her content. Though Qing’s live broadcasts focused on crime prevention, her call for virtual gifts in exchange for more detailed stories raised red flags.

Some saw it as a thinly veiled attempt to profit off her notoriety. In a society where online influence increasingly equates to economic success, Qing’s case reopened uncomfortable discussions about how far individuals—and platforms—are willing to go in monetizing personal history, even when it involves criminal activity.

The Fine Line Between Redemption and Exploitation

Qing Chenjingliang’s case embodies a complex tension in contemporary Chinese society—and indeed in the global digital age: the balance between personal redemption and public responsibility, between freedom of expression and ethical content creation.

Her efforts to educate the public about fraud are not without merit. She possesses a unique and painful perspective that could genuinely help people avoid falling prey to scams. But her mode of delivery, tied so closely to the branding of her former identity, blurs ethical boundaries.

The backlash she faced also reflects wider societal anxieties in China. There is growing discomfort with the influence of livestream culture, where internet personalities can attain rapid fame and fortune—sometimes based on controversial or even criminal pasts.

While the government has increasingly cracked down on content it views as harmful, the rapid evolution of online platforms often outpaces regulatory responses. Qing’s case, then, is not just about her—it is a symbol of larger debates over media ethics, punishment, and the public’s appetite for redemption narratives.

For some, Qing is a cautionary tale of how beauty and charisma can be used both for deceit and for storytelling, depending on the moment. For others, she is a woman who made mistakes and tried to change, only to find that society is less forgiving than it claims to be. Her ban from social media, regardless of whether one agrees with it, underscores how complicated it is to judge a person’s intentions in the internet age.

As of now, Qing has not issued any public response to her ban. Whether she will seek another platform or fade into anonymity remains to be seen. But her story has already left a mark on China’s collective consciousness, challenging public perceptions of crime, punishment, and the fragile space in which second chances exist.