The mass killing of over 300 ostriches at Universal Ostrich Farms in British Columbia has sparked shock, anger, and controversy across Canada and beyond. The cull, carried out under official orders to control the spread of bird flu, has now become the center of a growing storm after the farm’s owner alleged that the ostriches were deliberately targeted because they were involved in promising medical research.

The incident, which took place on November 6, has raised questions not only about disease control measures but also about the opaque intersection between science, government policy, and the protection of intellectual innovation in biotechnology. Katie Pasitney, co-owner of the farm, claims that the birds were healthy and had shown promising results in research aimed at developing antibody-based treatments derived from ostrich egg yolks. According to her, the ostriches were part of a pioneering program that had demonstrated potential effectiveness against major viruses, including COVID-19 and H1N1 influenza.

Her allegations — that a fabricated outbreak was used as a pretext to destroy the flock — have since fueled widespread debate and suspicion among animal rights advocates, conspiracy theorists, and independent scientists alike. The culling was ordered by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) after tests confirmed the presence of the H5N1 virus in two ostriches at the farm. But while officials have defended the move as a necessary biosecurity measure, the gruesome nature of the operation and the broader implications of Pasitney’s claims have ignited one of the most contentious animal health incidents in recent Canadian history.

A Research Project with Medical Promise

The Universal Ostrich Farms, located in British Columbia, had been running an unusual but ambitious biotechnology project. Pasitney’s mother, Karen Espersen, together with her research partner Dave Bilinski, had begun inoculating ostriches with inactive forms of the COVID-19 virus back in 2021. The goal was to harness the birds’ remarkable immune system to produce antibodies capable of neutralizing a wide range of viral pathogens.

Ostriches possess an exceptionally strong immune response, an evolutionary trait that allows them to survive in harsh and disease-prone environments. Their antibodies — called immunoglobulin Y (IgY) — are deposited in high concentrations in egg yolks, from which they can be extracted safely and non-invasively. These antibodies have been studied for their potential use in diagnostic kits, antiviral sprays, and even protective equipment such as masks and coatings.

Espersen told North Shore News in 2021 that their research had shown encouraging results. “We inoculated our hens with the dead COVID-19 virus,” she said at the time. “The hen produces antibodies in two weeks, and two weeks after that, she puts them into her eggs.” Within a month, their team could harvest eggs rich in antibodies that they believed could neutralize the virus. The farm’s research reportedly suggested up to 99.9 per cent neutralization efficacy against coronavirus particles in controlled laboratory conditions.

Between 900 and 1000 shots fired to take out approx 300 ostriches in a 3-4 hour span…

— THEWATCHTOWERS (@THEWATCHTOWERS) November 7, 2025

They terrorized these birds until the very end 💔https://t.co/QQJAOJuyxU pic.twitter.com/h1fyRp6Ttd

Pasitney and her mother were reportedly working toward developing commercial products such as nasal sprays and face masks embedded with these antibodies — a potentially revolutionary step in passive immunization and viral prevention. According to Pasitney, the project was moving toward commercialization when tragedy struck. “We were on a positive path and seeing results,” she said. “Then suddenly, after reaching out to the government for funding, we had an influenza outbreak.”

The implication — that the outbreak may have been induced or exaggerated to sabotage their progress — lies at the core of Pasitney’s conspiracy claim. She argues that their success posed a threat to larger pharmaceutical interests and government-backed research efforts, which may have prompted the eradication of the flock under the guise of disease control.

The Bird Flu Outbreak and the Mass Culling

The official account paints a different picture. In December of last year, the CFIA received reports that ostriches were dying at the Universal Ostrich Farms property. Samples were taken and subsequently tested positive for the H5N1 strain of avian influenza — a highly contagious virus that has devastated poultry industries around the world.

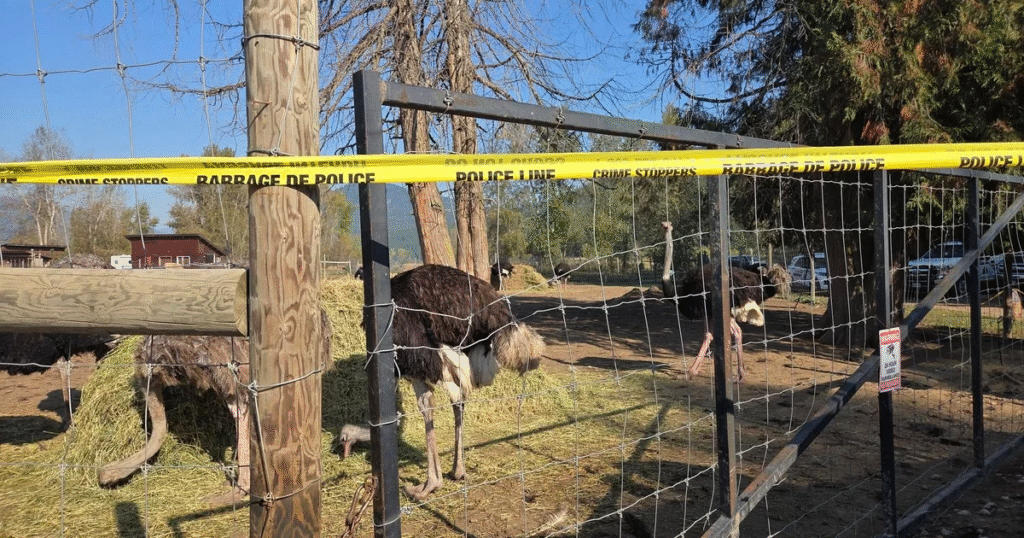

Standard protocol in such cases requires that all birds on the affected property be destroyed to prevent further spread. The CFIA determined that the entire flock — numbering over 300 ostriches — had to be culled. Pasitney and her mother attempted to challenge the order in court, arguing that the testing was flawed and that the birds should be quarantined and retested instead. However, their appeals were rejected by the Federal Court of Appeal in June 2025, which upheld the CFIA’s decision.

On November 6, a team of armed personnel arrived at the property to carry out the cull. According to Pasitney, the scene was “like a war zone.” She described how the ostriches, some over 35 years old and known to the family by name, were herded into a pen and shot dead. “They could have quarantined and monitored them, but they chose execution,” she told The Daily Mail.

Read : Hundreds of Ostriches Face Cull in Canada After Supreme Court Decision on Bird Flu Outbreak

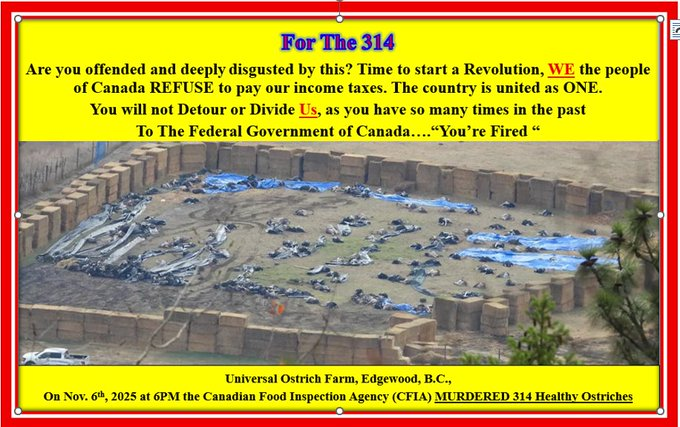

Photographs taken afterward showed rows of dead ostriches covered with tarps, while others lay with their heads severed. Pasitney said that some birds were still alive and suffering after the initial round of gunfire and were beheaded the next day. Her description has been corroborated by several disturbing images circulating online, which have fueled public outrage and calls for an independent inquiry.

The CFIA, in response, issued a statement defending its actions: “Given that the flock has had multiple laboratory-confirmed cases of H5N1 and the ongoing serious risks for animal and human health and trade, the CFIA is carrying out response activities at the infected premises.” The agency insisted that its team followed internationally recognized animal welfare and disease control standards.

However, critics argue that the CFIA’s procedures are outdated and excessively brutal, particularly when dealing with intelligent and long-lived animals like ostriches. Animal rights organizations have demanded a review of the culling protocols, emphasizing the need for more humane containment and testing methods before resorting to mass extermination.

Allegations, Conspiracy Theories, and Scientific Debate

Pasitney’s claim that the outbreak was a deliberate act of sabotage has added an explosive new dimension to the case. In her interview, she accused Canadian authorities of inducing the influenza outbreak soon after the farm sought government funding for their antibody research. “They didn’t want our therapeutic bodies out,” she said, referring to the antibodies derived from ostrich eggs. She maintains that the birds were healthy and that the supposed outbreak was either fabricated or contained to a negligible number of cases that could have been managed without a full-scale cull.

While there is no evidence supporting these claims, they have gained traction among groups distrustful of government agencies and pharmaceutical companies. The story has spread rapidly across social media platforms, where it has been framed as another example of suppression of independent scientific innovation. Conspiracy theorists have linked the incident to broader narratives about the control of medical technologies and the monopolization of pandemic-related research.

Experts, however, caution against jumping to conclusions. Virologists point out that H5N1 is an extremely contagious and lethal virus in birds, capable of crossing species barriers and infecting humans. In such cases, even a handful of positive test results can warrant drastic containment measures. Dr. Brian Wong, a veterinary epidemiologist based in Toronto, noted that “avian influenza can spread rapidly through large bird populations, and ostriches are not exempt from infection.”

Read : Boris Johnson Bitten by Ostrich at Dinosaur Valley State Park in Glen Rose: Watch

He added that while the killing of such a large number of animals is tragic, it is sometimes the only way to prevent a wider outbreak with potentially devastating consequences. Nevertheless, the lack of transparency in the CFIA’s testing and decision-making process has fueled ongoing mistrust. The agency has so far declined to release detailed laboratory data or address Pasitney’s specific allegations, citing privacy and ongoing procedural reviews. This silence has left room for speculation and fueled public skepticism.

From a scientific standpoint, ostrich-derived antibodies have indeed shown promise in early studies. Research teams in Japan and South Africa have explored similar applications, developing ostrich-egg-derived antiviral sprays and coatings. These studies support the biological plausibility of the Universal Ostrich Farms’ claims, lending a measure of credibility to the idea that their research could have been valuable. However, the assertion that government officials would intentionally engineer a viral outbreak to suppress such research remains unsubstantiated.

The incident has also exposed a broader tension between small-scale independent research ventures and national regulatory frameworks. While large pharmaceutical companies often have the resources to meet complex biosafety and approval requirements, smaller entities like Universal Ostrich Farms may find themselves vulnerable to shutdowns and strict enforcement when their work intersects with infectious disease control. The resulting asymmetry fuels perceptions of bias and suppression, even when official actions are legally justified.

As the public debate continues, animal welfare advocates and scientific transparency groups are calling for an independent investigation into the culling. They argue that the CFIA should disclose its full testing data, explain why less drastic containment options were not pursued, and assess whether the culling was proportionate to the risk posed.

Meanwhile, the farm’s owners say their research is effectively destroyed. “Our birds were not just livestock,” Pasitney said. “They were the heart of our work, our years of research, and our family.” The loss, she said, represents not only emotional devastation but the collapse of a project that could have contributed to pandemic prevention and viral therapeutics.

Whether the mass killing was a legitimate public health measure or an avoidable tragedy rooted in bureaucratic rigidity, the destruction of 314 ostriches has left an indelible mark on Canada’s agricultural and scientific landscape. The event underscores the fragile balance between biosecurity, innovation, and public trust — and raises haunting questions about what may be lost when those forces collide.

**mitolyn reviews**

Mitolyn is a carefully developed, plant-based formula created to help support metabolic efficiency and encourage healthy, lasting weight management.