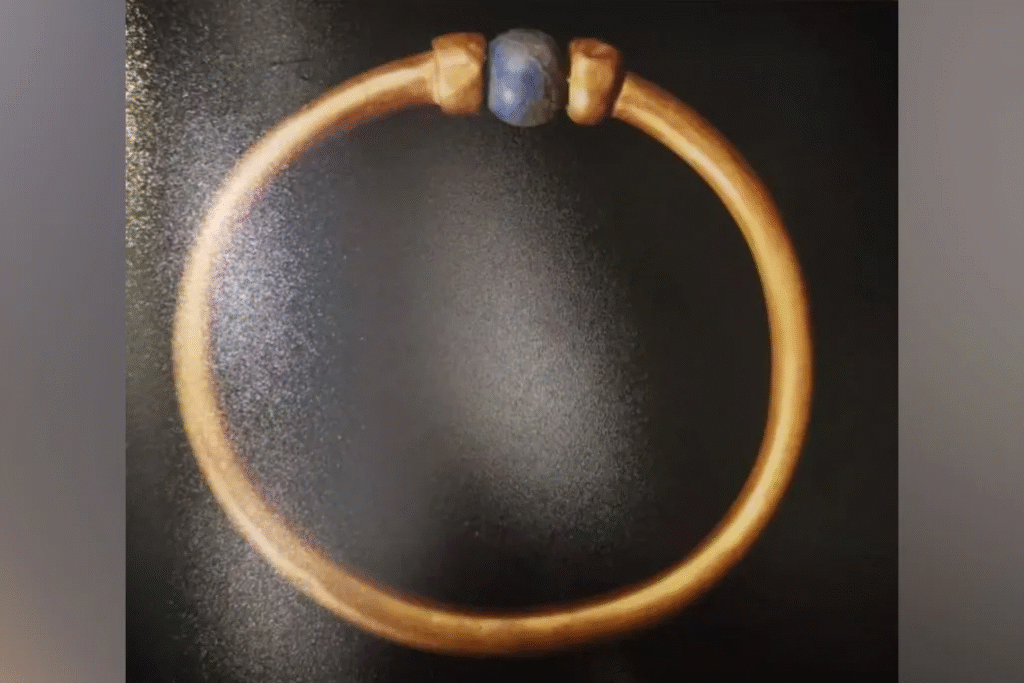

In a shocking revelation that has sent ripples through the global archaeological community, a priceless 3,000-year-old gold bracelet belonging to Pharaoh Amenemope has been confirmed stolen from Cairo’s iconic Egyptian Museum. The artifact, a delicate band of gold adorned with spherical lapis lazuli beads, vanished from the museum’s restoration laboratory on September 9, 2025.

What makes this incident particularly heartbreaking is not just the theft, but the irreversible destruction that followed: the bracelet was sold for a mere fraction of its cultural value and melted down into anonymous gold. As Egypt grapples with the loss of this irreplaceable piece of its ancient heritage, questions about museum security and the vulnerability of national treasures are coming to the forefront.

The Theft: From Museum Safe to Smelter’s Fire

The disappearance of the bracelet came to light amid routine preparations for an international exhibition. The Egyptian Museum, home to over 170,000 artifacts and the oldest archaeological museum in the Middle East, was gearing up to ship dozens of treasures to Rome for the upcoming “Treasures of the Pharaohs” exhibit scheduled for next month. As staff inventoried items in the restoration lab, the gold band—cataloged as part of Pharaoh Amenemope’s collection—failed to appear. It had been stored securely in a safe, accessible only to authorized personnel.

Egypt’s Tourism and Antiquities Ministry announced the theft on September 17, 2025, prompting an immediate nationwide alert. Images of the bracelet were disseminated to all Egyptian airports, seaports, and land border crossings in a bid to thwart any smuggling attempt. The ministry emphasized that the delay in public disclosure was intentional, allowing investigators to proceed without tipping off potential culprits. A specialized committee was swiftly formed to conduct a full inventory of the lab’s contents, ensuring no other artifacts had been compromised.

The investigation, led by Egypt’s Interior Ministry, uncovered a trail of betrayal that began within the museum’s own walls. The primary suspect is a restoration specialist employed at the facility, who confessed to extracting the bracelet from the safe on the day of the theft. Motivated by quick financial gain, the specialist contacted an acquaintance who owned a silver shop in Cairo’s bustling Sayeda Zeinab district. The intermediary then offloaded the item to the proprietor of a gold workshop in the city’s historic jewelry quarter for 180,000 Egyptian pounds—approximately $3,700 USD.

From there, the bracelet’s fate took a tragic turn. The workshop owner, sensing an opportunity, resold the ancient gold to a local smelter. Unaware or unconcerned with its provenance, the smelter melted it down alongside other scraps, recasting the precious metal into generic jewelry components. By the time authorities traced the chain of custody, the artifact’s unique form—its intricate gold band and the symbolic lapis lazuli beads representing the “hair of the gods” in ancient Egyptian lore—had been obliterated. The Interior Ministry confirmed this devastating outcome on September 18, 2025, stating that the bracelet was “lost forever.”

Read : Grand Egyptian Museum is Partially Open for Visitors After 20 Years

In a rapid response, four individuals were arrested: the restoration specialist, the silver shop owner, the gold workshop proprietor, and the smelter. Proceeds from the sale, totaling around 194,000 Egyptian pounds including subsequent transactions, were seized by police. The ministry released images of the suspects, underscoring the collaborative nature of the crime. While the arrests provide some measure of justice, they cannot undo the physical annihilation of a relic that had survived millennia.

Read : Exploring Ancient Wonders: Top Ten Selfie Spots in Egypt

This incident highlights the insider threats that plague cultural institutions. The Egyptian Museum, located in the heart of Tahrir Square, attracts millions of visitors annually, yet its restoration labs—often tucked away from public view—rely heavily on trust in staff. The theft’s detection during exhibition prep was fortuitous, but it raises alarms about routine vulnerabilities in artifact handling.

The Artifact’s Legacy: A Glimpse into the 21st Dynasty

At the heart of this scandal lies not just gold, but a tangible link to one of ancient Egypt’s enigmatic rulers: Pharaoh Amenemope, who reigned during the 21st Dynasty from 993 to 984 BCE. This era, part of the Third Intermediate Period, marked a time of political fragmentation following the grandeur of the New Kingdom. Power shifted northward to Tanis in the Nile Delta, where Amenemope established his capital, away from the traditional seat in Thebes. His rule, though brief, was characterized by efforts to consolidate authority amid rival priesthoods and foreign influences.

The stolen bracelet, a simple yet elegant band, was discovered in 1940 by French Egyptologist Pierre Montet during excavations at Tanis’ royal necropolis. Montet, working just months before the Nazi occupation of France, unearthed Amenemope’s tomb—a trove that included the pharaoh’s gilded wooden funerary mask, now a centerpiece of the Egyptian Museum’s collection.

The bracelet, likely a ceremonial or funerary adornment, exemplifies the era’s craftsmanship. Its gold, revered by Egyptians as the “flesh of the gods,” symbolized immortality and divine favor. The single spherical lapis lazuli bead, sourced from distant Afghanistan via ancient trade routes, evoked the night sky and the locks of hair belonging to deities like Hathor or Isis.

Though not the most ornate piece in the museum—experts like Egyptologist Jean Guillaume Olette-Pelletier have described it as “not the most beautiful”—its value transcends aesthetics. In the 21st Dynasty, jewelry served ritual purposes, warding off evil in the afterlife or affirming royal lineage. Amenemope’s artifacts, including the bracelet, offer insights into a pharaoh whose life is shrouded in mystery. Historical records mention him in the context of temple donations and diplomatic ties, but his tomb’s intact state provided rare, unlooted glimpses into elite burial practices.

The bracelet’s journey from Tanis to Cairo’s museum underscores Egypt’s archaeological triumphs and challenges. Discovered amid World War II tensions, it was transported to the Egyptian Museum in the 1940s, where it joined thousands of items chronicling 5,000 years of history. Funerary masks and jewelry from this period, like Amenemope’s, were often featured in global exhibitions, such as the 2022-2023 “Ramses the Great and the Gold of the Pharaohs” tour that showcased his mask. Losing the bracelet severs a thread in this narrative, depriving future generations of a direct connection to a ruler who bridged Egypt’s classical and late periods.

Implications and Outrage: Safeguarding Egypt’s Treasures

The melting down of Amenemope’s bracelet has ignited widespread fury in Egypt and beyond, amplifying calls for robust protections of cultural heritage. Social media platforms buzzed with outrage, as citizens decried the “betrayal” of national icons for petty profit. Prominent voices, including human rights lawyer Malek Adly, labeled the incident an “alarm bell for the government,” urging immediate reforms in museum security protocols. The scandal evokes painful memories of past losses, such as the 1977 theft of Vincent van Gogh’s Poppy Flowers from a Cairo museum—recovered once but stolen again in 2010 and still missing.

Egypt’s antiquities sector, while bolstered by recent initiatives like the 2021 royal mummies parade to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, faces persistent threats. The country repatriated 25 smuggled artifacts from the United States earlier this year, including temple fragments from Queen Hatshepsut’s reign, signaling international cooperation. Yet, internal thefts like this one expose gaps in oversight, particularly in restoration areas where artifacts are handled without constant surveillance.

In response, the Tourism and Antiquities Ministry has pledged enhanced measures: mandatory digital tracking for high-value items, expanded CCTV in labs, and stricter vetting of staff. The full inventory at the Egyptian Museum continues, with preliminary reports confirming no additional losses. Globally, the incident serves as a cautionary tale for institutions worldwide, from the Louvre to the British Museum, where repatriation debates rage. Egypt’s treasures, fueling a tourism industry that draws millions annually, are economic lifelines—yet their vulnerability underscores the need for ethical stewardship.

Ultimately, the destruction of this 3,000-year-old bracelet is a profound loss for humanity. It wasn’t just metal and stone; it was a whisper from Amenemope’s world, a testament to human ingenuity across epochs. As investigations wrap up and reforms take shape, the hope remains that such tragedies will steel Egypt’s resolve to protect its unparalleled legacy. For now, the pharaoh’s gold lives on only in photographs and records—a somber reminder that history’s guardians must be ever vigilant.