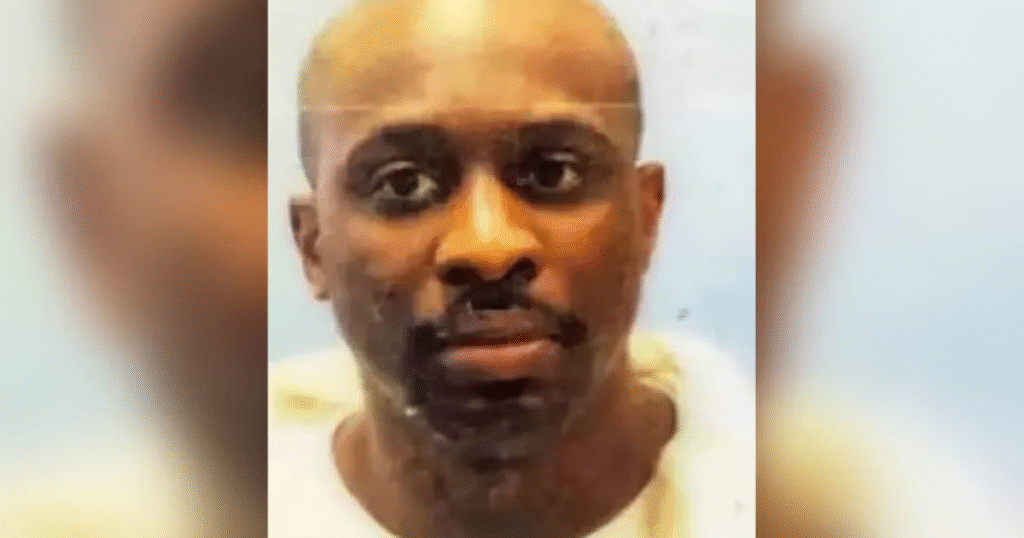

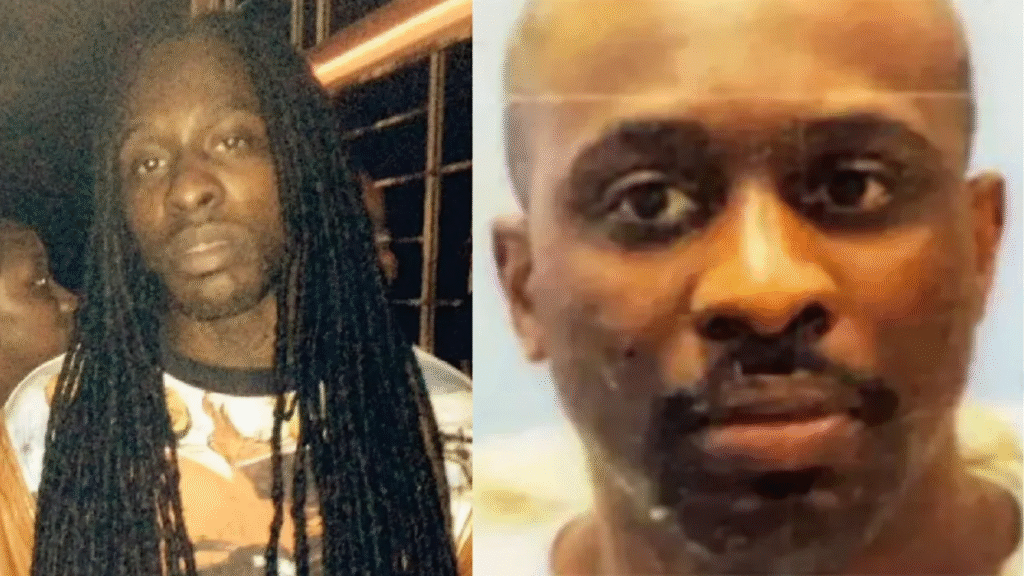

The U.S. Supreme Court has taken up a significant case testing the limits of religious freedom protections within America’s prison system. The case centers on Damon Landor, a former Louisiana inmate and follower of the Rastafari faith, whose decades-long dreadlocks were forcibly cut by prison officials in 2020.

Landor contends that the act violated his religious rights and now seeks financial damages under a federal statute designed to protect inmates’ religious practices. The outcome of Landor v. Louisiana Department of Corrections could reshape how courts interpret the ability of prisoners to hold officials accountable when their religious freedoms are violated, particularly under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA).

A Clash Between Religious Liberty and Institutional Immunity

When Damon Landor entered Louisiana’s prison system in 2020 for a five-month sentence, he carried not only his Rastafari faith but also a legal precedent. He brought with him a copy of an appeals court decision affirming that forcing inmates to cut dreadlocks for religious reasons violates federal law.

For Landor, whose dreadlocks had grown for nearly twenty years as a sacred expression of faith, this represented a safeguard against unwanted interference. Rastafarians believe that hair, particularly dreadlocks, symbolizes a divine covenant rooted in biblical teachings such as the Nazarite vow described in the Old Testament.

At his first two prison facilities, officials respected these beliefs. However, when Landor was transferred to the Raymond Laborde Correctional Center in Cottonport for the final weeks of his sentence, that respect abruptly ended. According to court records, a prison guard confiscated and discarded the legal ruling Landor carried. Shortly after, the warden ordered guards to shave his head. Two officers restrained Landor while a third forcibly cut off his dreadlocks, leaving his scalp bare.

Landor filed a lawsuit after his release, seeking monetary damages under RLUIPA. He argued that the act’s explicit purpose—to safeguard the religious exercise of incarcerated individuals—should allow victims to recover damages when those rights are egregiously violated. Lower courts, however, dismissed his claim. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals expressed sympathy for Landor’s ordeal but concluded that RLUIPA does not authorize financial compensation against prison officials, even in cases of clear misconduct.

Read : Three Prisoners Charged with Murder of Convicted Child Killer Kyle Bevan at HMP Wakefield

Louisiana has since amended its grooming policy to prevent similar incidents, but it continues to maintain that the law provides only for injunctive relief—orders to stop or prevent violations—not monetary damages. The state argues that expanding RLUIPA to include financial accountability could invite a flood of lawsuits and undermine prison management.

Before the Supreme Court, Landor’s case presents a fundamental question: when a prisoner’s religious rights are undeniably violated, should they have the right to seek compensation from those responsible?

The Legal Crossroads: Interpreting RLUIPA and Its Limits

The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 was enacted by Congress to ensure that individuals do not lose their religious rights simply because they are incarcerated. It prohibits governments from imposing substantial burdens on religious exercise unless those actions further a compelling governmental interest and are the least restrictive means of achieving it. The statute’s language mirrors that of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), passed in 1993, which applies to federal entities.

The Supreme Court’s deliberations in Landor v. Louisiana Department of Corrections thus revolve around a key interpretive issue: whether RLUIPA, like RFRA, allows individuals to recover money damages when their religious rights are violated.

In 2020, the Court ruled in Tanzin v. Tanvir that Muslim men placed on the FBI’s no-fly list for refusing to act as informants could sue federal agents personally under RFRA for monetary damages. That decision, supported by a unanimous Court, suggested that religious liberty laws should provide meaningful remedies for those harmed by government overreach. Landor’s legal team now argues that this reasoning should extend to RLUIPA, its “sister statute,” particularly since both were designed to offer robust protection against governmental infringement.

During two hours of oral arguments, the Court’s three liberal justices—Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson—appeared sympathetic to Landor’s position. Justice Sotomayor pointedly questioned how a law meant to safeguard religious liberty could fail to provide recourse for egregious violations. Justice Jackson echoed the concern, emphasizing that without a mechanism for damages, such protections risk becoming hollow.

However, the Court’s conservative majority, which would require at least two defections for Landor to prevail, appeared divided. Justice Amy Coney Barrett acknowledged the “egregious” nature of the incident but noted that lower courts have consistently interpreted RLUIPA as not authorizing monetary damages. Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts probed the broader implications of extending such remedies, expressing concern over potential interference in prison administration.

The Justice Department, notably, has switched positions since the Trump administration. Whereas it previously argued against allowing damages in the Tanzin case, it now supports Landor’s claim, asserting that denying compensation in cases of clear religious rights violations would undermine the purpose of RLUIPA.

Legal observers point out that while injunctive relief can prevent future violations, it offers no redress to those who have already suffered irreversible harm. For Landor, whose dreadlocks symbolized a sacred bond with his faith, the forced shaving represented not only a physical humiliation but a spiritual assault. His supporters argue that without the possibility of damages, prison officials face little deterrent against future misconduct.

The Broader Stakes for Religious Freedom in Prisons

The implications of Landor’s case extend far beyond his personal experience. Across the United States, incarcerated individuals of diverse faiths—Muslims, Sikhs, Jews, Native Americans, and others—depend on RLUIPA to protect their religious practices within prison walls. These rights encompass dietary restrictions, access to religious texts, observance of prayer rituals, and adherence to grooming standards rooted in faith.

The Rastafari religion, which emerged in 1930s Jamaica as a spiritual and political response to colonial oppression, holds particular reverence for natural living and divine connection through the body. Dreadlocks are considered a physical manifestation of this belief—a covenant with God and a rejection of Western norms of conformity. Icons such as Bob Marley and Peter Tosh helped spread the movement’s message of spiritual freedom and resistance to oppression. For many adherents, being forced to cut dreadlocks is not merely a grooming issue but an act that severs a sacred tie.

In the prison context, courts have long balanced such religious claims against institutional concerns about security and order. Yet, as Landor’s case demonstrates, when violations occur without justification, the lack of personal accountability leaves inmates with little remedy.

Advocates for religious liberty warn that denying financial damages effectively insulates prison officials from consequences, even when they act maliciously or in direct contravention of established law. They contend that robust protection of religious rights requires more than theoretical guarantees; it demands practical enforcement through compensatory mechanisms.

On the other hand, states argue that allowing damages under RLUIPA would open the door to an influx of lawsuits from prisoners, straining judicial resources and complicating prison management. They maintain that injunctive and declaratory relief already ensure compliance with religious rights without imposing personal financial liability on officers acting in their official capacity.

This debate mirrors broader tensions in American jurisprudence over the intersection of religious freedom and government immunity. If the Court sides with Landor, it could mark a significant expansion of the remedies available under RLUIPA, potentially exposing state officials to personal lawsuits for religious rights violations. If it rules against him, the decision would reaffirm the prevailing view that the statute provides only prospective relief—leaving individuals like Landor without compensation for past harm.

Awaiting a Decision with Far-Reaching Consequences

As the Supreme Court deliberates, both advocates and critics recognize that Landor v. Louisiana Department of Corrections could set a transformative precedent for religious freedom within the correctional system. The case asks not only whether RLUIPA permits damages but also whether the nation’s highest court is willing to extend the same level of protection for state prisoners as it has for individuals challenging federal action under RFRA.

Justice Barrett’s acknowledgment of the “egregious” nature of the incident underscores the human dimension at the heart of the legal question. While the Court’s conservative bloc has often favored limiting governmental liability, several justices have also demonstrated a strong commitment to protecting religious liberty in recent years. That dynamic introduces uncertainty into the outcome, leaving room for potential crossover votes that could produce a narrow but consequential ruling.

Landor’s story resonates as part of a broader narrative about the struggle for dignity and faith behind prison walls. His experience reflects the vulnerability of incarcerated individuals whose religious identities are often at the mercy of institutional discretion. The eventual ruling, expected by spring, will determine not only whether Landor can seek financial compensation but also how future courts interpret the reach of religious liberty protections for inmates across the United States.

Whatever the outcome, Landor v. Louisiana Department of Corrections highlights a central tension in American law: the challenge of ensuring that constitutional and statutory guarantees of religious freedom remain meaningful even for those who live behind bars. For the Rastafarian community and other faith groups, the case represents a critical test of whether the justice system will recognize the profound spiritual harm inflicted when sacred expressions of belief are violated without recourse.

As the nation awaits the Court’s decision, one question looms large: can the promise of religious liberty truly endure in places where the state exerts near-total control over the body and spirit? The answer, to be delivered in the coming months, will reverberate far beyond Louisiana’s prison walls, shaping the contours of faith and freedom for years to come.