For centuries, the potato and tomato have occupied distinct places on our plates and in our minds — one a starchy, soil-dwelling staple often served fried, mashed, or baked; the other a juicy, sun-ripened fruit integral to salads, sauces, and Mediterranean cuisine.

But in a remarkable twist of evolutionary history, scientists have discovered that these two culinary icons share more than just the spotlight in global diets. New research reveals that the potato, beloved in dishes around the world, actually evolved from a tomato ancestor through an extraordinary natural hybridisation event that occurred nearly 9 million years ago.

This discovery challenges long-held perceptions in both botany and food science and opens up fascinating new avenues for agriculture, genetics, and plant breeding. What began as an effort to understand the origins of tuber formation has now turned into a revelation that has stunned even the most seasoned experts in evolutionary biology.

Tomato is Mother of Potato ?

At first glance, the idea that a potato could be descended from a tomato seems almost absurd. After all, tomatoes grow red, fleshy fruits above ground, while potatoes develop brown, knobby tubers underground. Their culinary uses couldn’t be more different. But from a genetic standpoint, the two plants — along with eggplants and tobacco — all belong to the Solanaceae family, known for its diversity of species and traits.

The groundbreaking study, conducted by researchers led by Professor Sanwen Huang at the Agricultural Genomics Institute in Shenzhen, China, turned the scientific community’s attention toward the Andean region of South America. It’s here that wild tomatoes and a plant called Etuberosum coexisted millions of years ago. The key to their findings? A phenomenon known as hybridisation, where two different plant species naturally crossbreed and exchange genetic material.

Read : Tomatoes and Watermelon Can Help Cure Depression Naturally: Chongqing Medical University

The research team analysed 450 genomes from cultivated potatoes and 56 genomes from wild relatives, creating one of the most extensive genomic datasets of its kind. What they discovered was extraordinary: an ancient wild tomato species crossed with Etuberosum and formed a completely new lineage — the early potato ancestor.

Read : What do you think Tomato is Fruit or Vegetable?

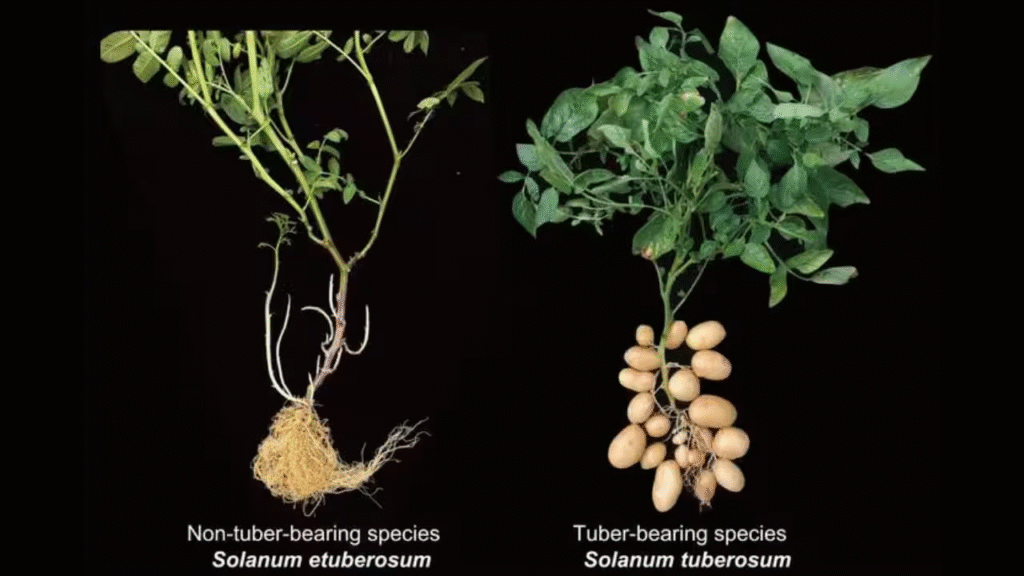

“Tomato is the mother and Etuberosum is the father,” explained Professor Huang. But, as he noted, this wasn’t obvious at first. Above ground, the potato plant strongly resembles Etuberosum, but underground, the game changes entirely. Etuberosum lacks the hallmark potato tubers, instead bearing thin roots. The clue to the mystery lay in the tomato’s DNA.

The Genetic Spark Behind the Tuber Revolution

What truly sets the potato apart from its relatives is its ability to form tubers — nutrient-packed underground organs that allow the plant to store energy and reproduce asexually. This adaptation has made the potato one of the most successful and resilient crops in human agriculture. But how did this trait emerge if neither Etuberosum nor the tomato produces tubers on their own?

The answer lies in two specific genes: SP6A, which is present in tomatoes, and IT1, found in Etuberosum. On their own, these genes don’t do much in terms of tuber formation. But together — and only together — they trigger the cellular changes that transform ordinary underground stems into energy-dense tubers.

This synergy between SP6A and IT1 is a biological masterpiece. The hybridisation event that fused these genes in a shared genome gave rise to a unique trait — a brand-new organ, the tuber. It was, in evolutionary terms, an explosive moment. According to Harvard professor James Mallet, “It shows how a hybridisation event can spark the emergence of a new organ – and even lead to a new lineage with many species.”

What followed was a burst of evolution. As the Andes mountains rose, the newly formed potato species adapted to the changing high-altitude climate. The tubers offered a survival advantage, allowing the plants to store energy through drought and cold. Unlike seeds, tubers didn’t need pollinators. They could simply sprout into new plants — clones of the parent. This not only enhanced survival but also led to a stunning diversification of potato species across South America.

Indigenous people of the Andes played a critical role in shaping the potato’s future. They domesticated and cultivated varieties that produced larger, more palatable tubers. Today, there are hundreds of native potato varieties still grown in the region — a testament to ancient agricultural knowledge and adaptation.

A Legacy of Resilience and Future Possibilities

The potato’s journey from a wild hybrid to a global food staple is nothing short of epic. After being domesticated in the Andes, potatoes traveled with Spanish explorers to Europe in the 16th century. Initially feared and misunderstood — they weren’t mentioned in the Bible and they grew underground — potatoes soon proved themselves indispensable. Their durability in poor soils and high yields made them a lifeline for European populations, especially during times of scarcity.

In today’s world, the potato continues to be a crucial crop, feeding more than a billion people. Yet, the discovery of its origin has implications that go beyond historical interest. It’s already inspiring scientific projects aimed at improving agricultural practices and developing new plant varieties.

For instance, Professor Huang and his team are exploring how to manipulate the same genes — SP6A and IT1 — to induce tuber formation in other plants. One experimental project is even attempting to insert these potato genes into tomatoes, potentially creating a tomato plant that can grow edible tubers underground. If successful, this could revolutionize food production by combining the fast-growing fruit of the tomato with the energy-storing capacity of potatoes.

Moreover, the team is working on making potatoes more resilient by breeding varieties that reproduce through seeds. Unlike traditional potato farming, which relies on tubers (which are bulky and vulnerable to disease), seed-grown potatoes could be easier to store, transport, and distribute — especially in regions facing food insecurity or harsh climates.

This evolution-informed approach might also help overcome the genetic limitations of modern potatoes, which are often clonally propagated and thus genetically uniform. A narrow genetic base makes crops vulnerable to diseases — such as the late blight that caused the Irish Potato Famine in the 19th century. Broadening the potato’s gene pool using insights from its wild ancestors could enhance resilience and productivity.

In the long term, understanding the genetic architecture of traits like tuberisation may also help scientists in their quest to engineer climate-adapted crops. As global temperatures rise and growing conditions become more unpredictable, crops that can thrive under stress will be key to global food security.

The revelation that the potato is the offspring of a tomato and a little-known plant named Etuberosum is a profound reminder of how nature works in complex, surprising ways. What may seem like everyday foods to us — fries, stews, ketchup, salads — are built on millions of years of evolutionary innovation.

This mind-blowing discovery has not only rewritten the evolutionary history of a staple crop but has also sparked new possibilities for future food systems. Whether it’s through genetically informed breeding, synthetic biology, or experimental hybrid plants, the legacy of that 9-million-year-old love story between a tomato and Etuberosum is far from over.

In fact, if researchers have their way, the tomato might once again play a central role in shaping the future of the potato — turning the circle of life into a delicious twist of destiny.