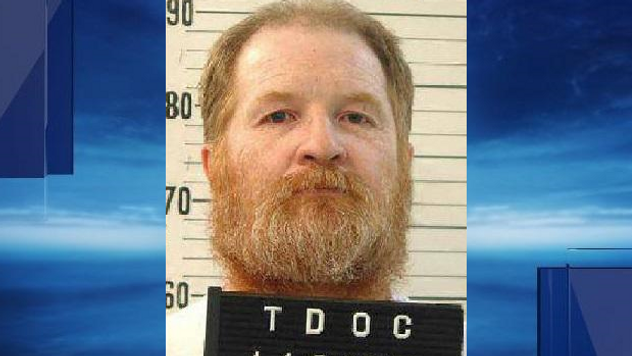

Harold Wayne Nichols, a long-serving death row inmate in Tennessee, has again drawn attention to the state’s complex capital punishment system after refusing to choose between two execution methods — electrocution and lethal injection. The 62-year-old convict, who has spent more than three decades on death row, is scheduled to die on December 11 for the brutal 1988 rape and murder of a college student in Chattanooga.

His decision not to choose means the state will proceed with its default method of execution: lethal injection. The case has reignited debate over Tennessee’s execution procedures, the reliability of its lethal injection protocol, and the enduring ethical questions surrounding the death penalty in the United States.

A Violent Crime That Shattered a Community

Harold Wayne Nichols was sentenced to death in 1990 for the rape and murder of 21-year-old Karen Pulley, a student at Chattanooga State University. The crime occurred two years earlier, in 1988, when Nichols lured Pulley into his car under the guise of offering help. Instead, he drove her to a remote area, where he sexually assaulted and murdered her. The killing shocked the Chattanooga community and underscored growing fears about violence against women in the area during that time.

Evidence presented during Nichols’ trial was damning. DNA and forensic findings, along with Nichols’ own confession, left little doubt about his guilt. Beyond the Pulley case, he admitted to a series of other rapes committed in the same region, revealing a pattern of violent sexual assaults that spanned several years. During his trial, Nichols expressed remorse and acknowledged the gravity of his crimes, yet he also admitted that he might have continued his violent behavior had he not been apprehended.

Nichols’ conviction placed him among Tennessee’s most notorious death row inmates. His long legal journey has mirrored the state’s shifting attitudes toward capital punishment, as lawmakers, courts, and governors have grappled with the logistics and morality of carrying out death sentences. Over time, his case became emblematic of the bureaucratic and ethical complications that surround the administration of the death penalty in America’s modern era.

A History of Delays and Controversies Over Execution Methods

Nichols’ upcoming execution date is not his first. He was previously scheduled to die in August 2020, but the execution was halted after then-Governor Bill Lee granted a temporary reprieve due to the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, Nichols had opted for electrocution, which Tennessee allows for inmates whose crimes occurred before January 1, 1999. The choice reflected growing skepticism among death row prisoners about the reliability and humaneness of the state’s lethal injection procedures.

Tennessee’s history with capital punishment has been fraught with controversy, particularly concerning the methods it employs. Until recently, the state used a three-drug combination in its lethal injection protocol: midazolam (a sedative), vecuronium bromide (a paralytic), and potassium chloride (to stop the heart). Attorneys for death row inmates repeatedly challenged this cocktail, arguing that it risked causing extreme pain and violated constitutional prohibitions against cruel and unusual punishment.

Those concerns gained significant traction when, in 2022, Governor Lee temporarily paused all executions following revelations that the Department of Correction had failed to properly test the chemicals used in its lethal injection process. An independent review confirmed that none of the drugs prepared for Tennessee executions between 2018 and 2022 had undergone the required testing to ensure safety and potency. As a result, the state suspended scheduled executions, including a second execution date for Nichols, while officials undertook a comprehensive overhaul of execution procedures.

Read : 44-Year-Old Stephen Bryant Who Wrote Messages in Victim’s Blood Chooses Execution by Firing Squad

In December 2023, Tennessee introduced a new execution protocol based on the single-drug method using pentobarbital, a powerful barbiturate that causes death through respiratory arrest. The change was intended to address earlier procedural failings and simplify the process. However, it has sparked fresh litigation. Attorneys representing several inmates have filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality and transparency of the new protocol, claiming that the state still refuses to disclose crucial information about the source and testing of the drug.

Read : Gaming Giants: The Top 10 Most Played Games Worldwide

The trial for that case is expected to begin in April 2026, long after Nichols’ scheduled execution date. By law, Tennessee inmates convicted before 1999 retain the right to choose between lethal injection and electrocution. If they decline to make a choice, lethal injection becomes the default method. Nichols’ current refusal to choose, therefore, effectively signals acceptance of the new protocol, unless he changes his decision within the two-week window granted by state regulations.

The Broader Debate on Death Penalty Ethics and Procedure

Nichols’ case highlights not only the personal fate of one convicted murderer but also the broader and ongoing national debate over how — and whether — the state should carry out executions. Tennessee remains one of a dwindling number of U.S. states that actively maintain the death penalty and use both lethal injection and the electric chair. Over the past decade, only five electrocutions have taken place nationwide, all of them in Tennessee.

The electric chair, once a symbol of modern justice in the 20th century, has largely fallen out of use due to growing recognition of its brutal and often botched outcomes. Inmates subjected to electrocution have sometimes suffered visible burns, muscle contractions, and prolonged deaths, prompting human rights advocates to label the practice inhumane. Nevertheless, some Tennessee inmates continue to request electrocution, perceiving it as a more predictable — or at least faster — method than the state’s uncertain lethal injection procedures.

Lethal injection, introduced in the 1980s as a supposedly more humane alternative, has itself been mired in scandal and dysfunction. Across the United States, executions using poorly mixed or contaminated drugs have led to prolonged suffering and public outrage. Pharmaceutical companies have increasingly refused to sell their products for use in executions, forcing states to turn to compounding pharmacies and secretive suppliers. This has fueled transparency lawsuits and ethical objections from medical professionals and human rights groups alike.

In Tennessee’s case, the switch to a single-drug protocol using pentobarbital was designed to minimize complications and align with the practices of states such as Texas and Missouri, where the method has been used for years. Yet, even pentobarbital has drawn scrutiny: autopsies of executed prisoners have shown signs of pulmonary edema — fluid buildup in the lungs — suggesting that inmates may experience sensations akin to drowning before death.

For Nichols, these competing issues of method, legality, and morality converge at a deeply personal level. His refusal to choose between the electric chair and lethal injection may reflect uncertainty, defiance, or resignation after decades of appeals and procedural delays. While his guilt has never been in doubt, the question of how the state should end his life remains a matter of contention, not only within Tennessee’s justice system but across a nation increasingly divided over the future of capital punishment.

Public opinion in Tennessee remains relatively supportive of the death penalty compared to national averages, but attitudes are shifting. Several recent polls show declining approval for executions, especially amid concerns about wrongful convictions, racial disparities, and procedural errors. Legal scholars note that the state’s death row population — currently numbering just over 40 inmates — has aged significantly, with many prisoners awaiting execution for more than 30 years. These long delays raise constitutional and ethical questions about whether prolonged confinement under threat of death constitutes its own form of cruelty.

The Tennessee Department of Correction, meanwhile, insists that it has rectified past failures and that the current protocol ensures both legality and dignity. Spokesperson Dorinda Carter stated that Nichols still has a two-week period to reconsider his choice of execution method before the December 11 date. If no change is made, preparations will proceed for lethal injection. Officials have not disclosed where the execution will occur, but it is expected to take place at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution in Nashville, where the state conducts all executions.

As Nichols’ execution date nears, advocacy groups are likely to renew calls for clemency or for further investigation into the state’s revised lethal injection process. While such appeals rarely succeed, they reflect enduring concerns about the opaque nature of execution protocols and the ethical responsibilities of the state. Nichols’ case, rooted in a heinous crime more than three decades old, now stands at the intersection of law, morality, and administrative precision — a reminder that the death penalty, even when legally sound, remains fraught with questions that go far beyond guilt or innocence.

The events leading to December 11 will thus serve as a test for Tennessee’s newly restructured execution system and, more broadly, for America’s ongoing reckoning with the machinery of death. Whether Nichols ultimately reconsiders his decision or not, his case underscores the profound complexities that accompany the state’s ultimate punishment — a process that, for all its procedural order, continues to stir unease in the public conscience.