Six months after a predawn hit-and-run crash ended the life of a well-known New Orleans bartender, a criminal court judge has imposed a nine-year prison sentence on the teenage driver who fled the scene. The case, which unfolded against the backdrop of the French Quarter’s nightlife and the city’s long-running struggle with traffic safety, drew intense scrutiny from the victim’s family, prosecutors, and advocates who argued that leaving an injured person without aid compounded the tragedy.

At the center was Michael Milam, a 36-year-old bartender who had recently relocated from Houston and was biking home from work when he was struck and left to die. The sentencing of Thomas Riggio, 19, capped a case marked by questions about accountability, intoxication, and whether a driver’s decision to stop—or not—can alter the course of justice as much as the collision itself.

The Fatal Crash and the Decision to Flee

Michael Milam had moved to New Orleans only weeks before his death, quickly securing a position at Café Lafitte in Exile, one of Bourbon Street’s oldest and most prominent gay bars. Known in Houston’s LGBTQ+ community as an award-winning bartender, Milam had built a reputation for professionalism and warmth. In the early morning hours of July 12, shortly after 4 a.m., he was riding his bicycle home from work through the Bywater neighborhood. As he attempted to turn onto Alvar Street at St. Claude Avenue, he was struck by an Infiniti driven by Thomas Riggio.

The impact proved fatal. Prosecutors said Riggio did not stop to render aid or call for help. Instead, he drove away from the scene, leaving Milam gravely injured in the roadway. Passengers in the vehicle later told investigators that Riggio promised he would report the crash, but hours passed before any contact with authorities. By then, Milam had died.

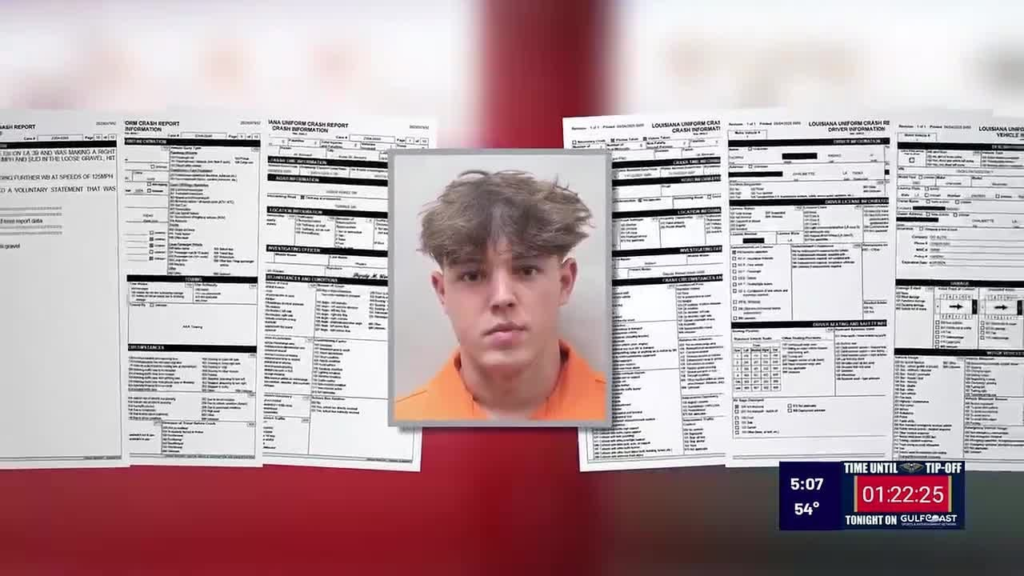

Riggio was booked into the Orleans Justice Center later that day. A toxicology test conducted roughly 12 hours after the collision showed a blood-alcohol concentration of 0.07 percent, just below Louisiana’s legal limit. The test also detected cocaine in his system. Prosecutors emphasized that the timing of the test meant Riggio’s intoxication at the moment of the crash could have been higher than the results indicated.

Read : Man Orders McDonald’s Burger With “Everything Removed,” Gets Empty Box With $19.81 Bill

The charge ultimately brought against Riggio—one felony count of hit-and-run driving causing death—reflected the prosecution’s focus on his failure to stop. While some members of Milam’s family believed the charge did not fully capture the gravity of the conduct, the statute carried a maximum sentence of 10 years. By pleading guilty as charged, Riggio avoided trial and placed his fate in the hands of Criminal District Judge Kimya Holmes.

Courtroom Testimony, Evidence, and the Judge’s Findings

The sentencing hearing brought emotional testimony from Milam’s siblings, who described the loss of a brother they said was central to their family and beloved by friends and coworkers. They spoke about his recent move, his excitement about New Orleans, and the sense that his life had been abruptly and needlessly cut short. Their statements also addressed their reaction to evidence prosecutors submitted in advance of the hearing, including a transcript of a recorded jail call made by Riggio hours after the crash.

According to the prosecution, Riggio’s demeanor during the call reflected a lack of urgency or concern for the victim. He reportedly downplayed how long he expected to be detained, a tone that prosecutors characterized as cavalier. The transcript was filed to counter the defense’s portrayal of a remorseful teenager overwhelmed by the consequences of a terrible mistake.

Read : Who Is Shireen Afkari, the Strava Employee Fired After Viral Altercation With Hazie’s Bartender?

Riggio took the witness stand before sentencing to apologize directly to the family. He acknowledged leaving the scene and told the court he had wanted to look Milam’s relatives in the eye to express remorse, adding that he had been advised against doing so earlier. He referenced his own siblings as he tried to convey the depth of his regret, stating that he could not imagine losing one of them in the way Milam’s family had lost their brother.

Defense attorney Roger Jordan urged Judge Holmes to impose probation rather than prison time, arguing that Riggio was young, had accepted responsibility through his guilty plea, and could be rehabilitated without incarceration. The request stood in contrast to the family’s plea for the maximum sentence allowed by law.

Judge Holmes rejected the call for leniency. In remarks delivered from the bench, she focused on the decision to flee rather than the collision itself. She said she did not accept Riggio’s early claim that he did not know what he had struck, noting that the circumstances demanded he stop and check. Holmes emphasized that the law requires drivers involved in serious crashes to render aid and contact authorities, a duty she described as fundamental.

The judge also reviewed Riggio’s prior driving history, which included incidents of reckless behavior. Records showed that he had previously struck another vehicle while performing doughnuts and, in a separate case, had sped into a ditch. Holmes described a pattern of escalating conduct, concluding that the fatal crash was not an isolated lapse but part of a broader trajectory of risk-taking behind the wheel.

In delivering the sentence, Holmes underscored the consequences of failing to stop. She said that had Riggio remained at the scene, the outcome—for both families—might have been different. The statement was not framed as speculation about Milam’s survivability, but as an observation about responsibility and the chain of events set in motion by the decision to flee.

Sentencing Outcome and Broader Implications

Judge Holmes sentenced Riggio to nine years in prison, one year short of the statutory maximum. He was given credit for time already served. After the sentence was pronounced, deputies placed Riggio in shackles as members of both families exited the courtroom.

The outcome did not fully satisfy everyone affected by the case. Some of Milam’s siblings maintained that the charge itself was too lenient and questioned whether Riggio’s family connections, including a stepfather in the St. Bernard Parish Sheriff’s Office, influenced how the case was handled. Prosecutors did not substantiate those suspicions, and the court record reflects that the sentence fell near the top of the permissible range.

For advocates focused on traffic safety, the case highlighted the persistent danger faced by cyclists and pedestrians, particularly in areas where nightlife and early-morning traffic intersect. Milam was biking home from work at an hour when impaired driving is more common, a factor that has prompted renewed calls for enforcement and infrastructure improvements in New Orleans neighborhoods beyond the French Quarter.

Legally, the sentence reinforced the seriousness with which courts treat hit-and-run offenses resulting in death. While intoxication can elevate charges in some cases, Louisiana law places distinct emphasis on the duty to stop and render aid. The nine-year term signaled that fleeing the scene can carry consequences approaching those imposed for more overtly violent crimes, even when a defendant is young and pleads guilty.

For Milam’s family, the hearing marked a painful milestone rather than a conclusion. Testimony underscored the enduring absence left by a brother who had only just begun to build a new life in New Orleans. For Riggio, the sentence closed one chapter while opening another defined by incarceration and the long-term repercussions of a single night’s decisions.

This content is really helpful, especially for beginners like me.