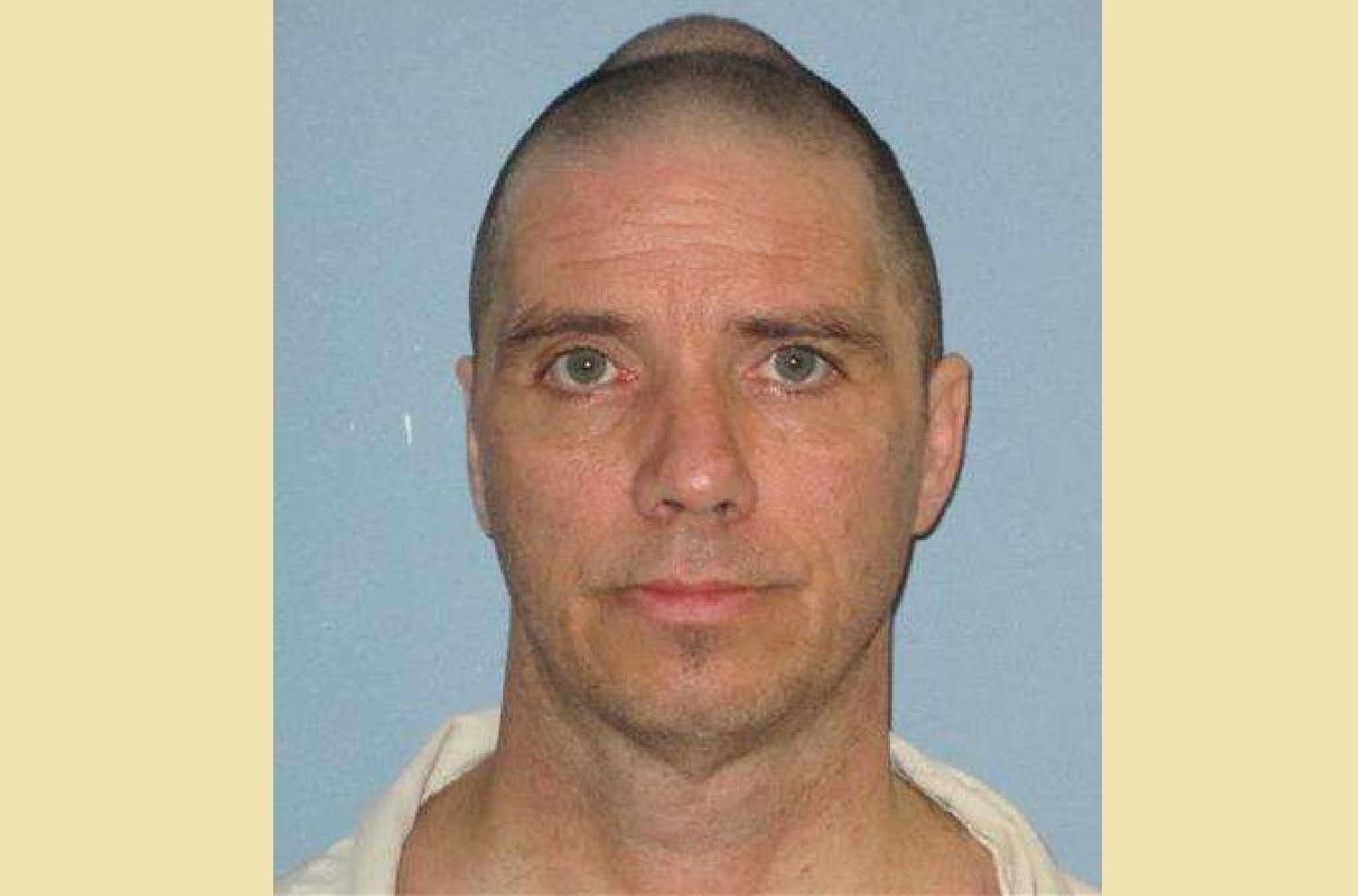

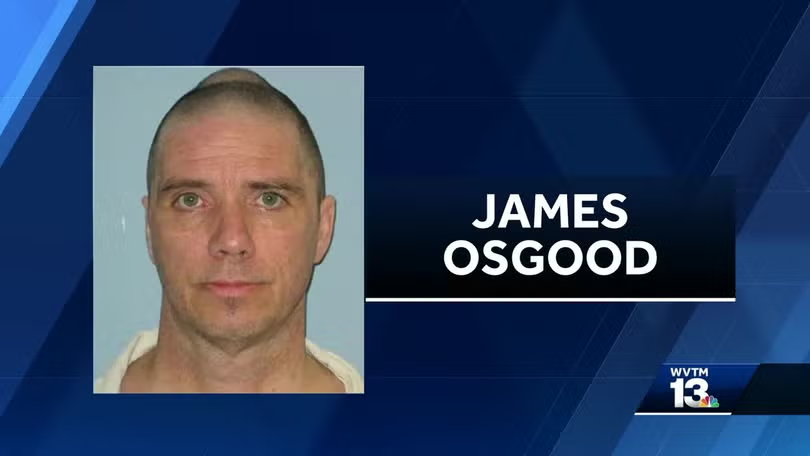

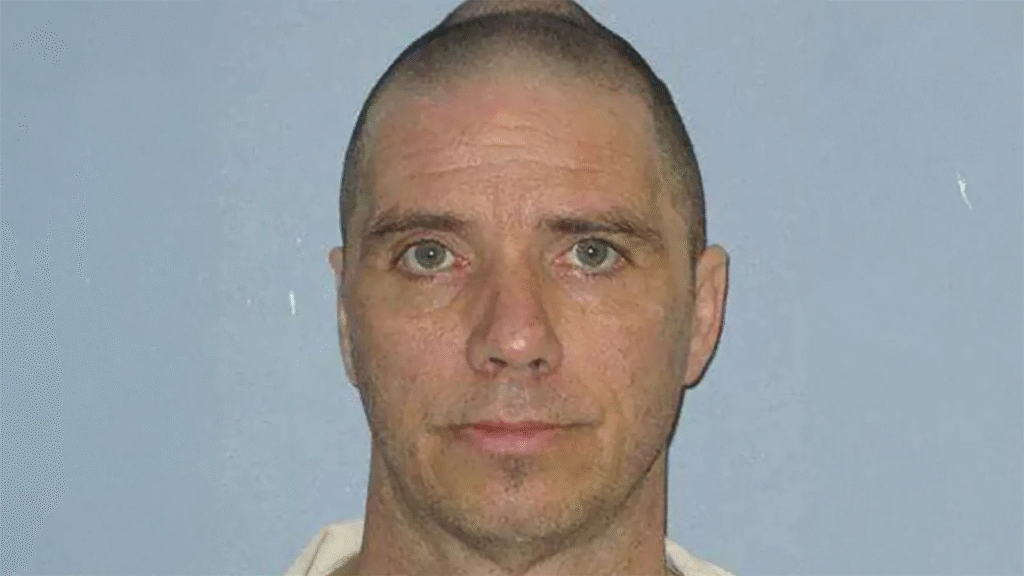

James Osgood, a 55-year-old inmate on Alabama’s death row, is set to be executed by lethal injection at 6pm on Thursday at William Holman Correctional Facility in Atmore. His crime—a brutal rape and murder committed 15 years ago—left deep scars on a community and devastated the family of the victim, Tracy Lynn Brown.

But in a rare twist, it is not the state pushing for Osgood’s execution. It is Osgood himself. After years of legal back-and-forth, he dropped his appeals and Asked for His Own Execution to be carried out, saying he’s guilty and tired of “wasting everybody’s time.”

James Osgood’s admission of guilt has added a disturbing layer of clarity to a crime already marked by horror. He told reporters recently that he accepts full responsibility for what he did and believes his life is now forfeit. “I’m a firm believer in, like I said in court, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” Osgood said.

“I took a life so mine was forfeited.” His decision to halt his legal appeals and accept execution sets him apart from most others on death row and places him among the roughly one in ten condemned inmates who have voluntarily sought their own deaths.

A Crime of Cruelty and Confession

The crime took place in 2010 when Brown’s lifeless body was discovered in her home, the victim of a gruesome sexual assault and murder. James Osgood, along with his girlfriend—who was also Brown’s cousin—forced Brown into sexual acts before Osgood slit her throat. Prosecutors detailed how the couple had fantasized about kidnapping and torturing someone, and tragically, they acted on those fantasies.

In court, the horror of the crime was evident not only in the prosecution’s narrative but in the voices of the victim’s family. “I can’t imagine anyone doing that to someone, even their worst enemy,” Brown’s stepmother told the judge at sentencing. The crime shocked Chilton County, and Osgood was convicted by a jury and sentenced to death. His girlfriend, meanwhile, received a life sentence.

Despite the brutality of the act, the trial also revealed the complexity of Osgood’s life. The judge noted that he had a deeply troubled childhood filled with trauma, including abandonment, sexual abuse, and a suicide attempt. But those factors, while tragic, did not absolve him of the crime.

Read : Inmate Arrested for Suspected Murder of John Mansfield at HMP Whitemoor

In the judge’s view, James Osgood’s active role in the killing, especially his decision to cut Brown’s throat and stab her while she pleaded for her life, warranted the harshest penalty under the law.

Read : First Human Head Transplant Surgery Could Be Just 8 Years Away

In the years that followed his conviction, Osgood engaged in a series of legal appeals. But at his 2018 resentencing—prompted by an earlier ruling that jurors received improper instructions—Osgood again took the opportunity to express remorse and request execution. “I didn’t want the families to have to sit through another hearing,” he said.

Seeking Death as a Form of Responsibility

The decision to ask for one’s own execution is rare but not unheard of in the American justice system. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, at least 165 people have volunteered for execution since the death penalty was reinstated in 1977. Most of these individuals had histories of mental illness, substance abuse, or long-standing suicidal ideation.

In James Osgood’s case, he articulated his reasoning in personal and painful terms. He said he no longer feels like he is “even existing” and wants to take full responsibility for the pain he caused. In a letter to his attorney, he wrote that continuing to live was only prolonging suffering—for himself, the victim’s family, and even the legal system. “I don’t believe in sitting here and wasting everybody’s time and everybody’s money,” he told the Associated Press.

His choice places him in a category often referred to as “volunteers” on death row—prisoners who waive their legal rights and speed up their own executions. While their motives vary, many cite remorse, despair, or exhaustion. James Osgood’s statements suggest a combination of all three.

In his final days, he has spoken publicly about the guilt he carries and the regrets that follow him. “I would like to say to the victim’s family, I apologize,” James Osgood said last week. “I’m not going to ask their forgiveness because I know they can’t give it.” He added that only God could offer such forgiveness, reflecting perhaps a belief in divine judgment and a spiritual accounting that now awaits him.

A System Marked by Complexity and Contradiction

The death penalty remains one of the most controversial aspects of the American justice system. In Alabama, executions are carried out with regularity, and the state has rarely granted clemency.

In fact, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey made headlines recently when she commuted the death sentence of Robin “Rocky” Myers to life in prison—the first such clemency granted by any Alabama governor since 1999.

In James Osgood’s case, however, there has been no such intervention. Given his insistence on carrying out the sentence, there appears to be little legal or political will to halt the process. And while Osgood’s past trauma and mental health issues were acknowledged during his trial, they did not outweigh the nature of his crime.

His case highlights a contradiction in the system: the balance between justice for the victim, compassion for the accused, and the societal implications of state-sponsored executions. It also brings into focus the emotional toll these cases take—not only on victims’ families but on everyone involved, from attorneys and judges to prison staff and journalists.

There are those who believe that allowing an inmate to choose death is a form of psychological relief, while others argue it is yet another failure of a system that doesn’t invest enough in mental health support and rehabilitation. James Osgood’s statements about his own life—his weariness, his loss of purpose, his desire to “stop existing”—could be seen as symptoms of profound psychological despair.

At the same time, his unwavering confession and refusal to seek forgiveness from those he’s hurt suggests a man who has made peace with his guilt but not with redemption. He isn’t asking for sympathy, only for the process to end.

As the execution hour approaches, the finality of James Osgood’s fate looms. His death will add to a growing list of those who not only committed a terrible crime but chose to meet justice without resistance. In that sense, his story is one of both tragedy and acceptance—a life that began with suffering, ended with violence, and now concludes with surrender.