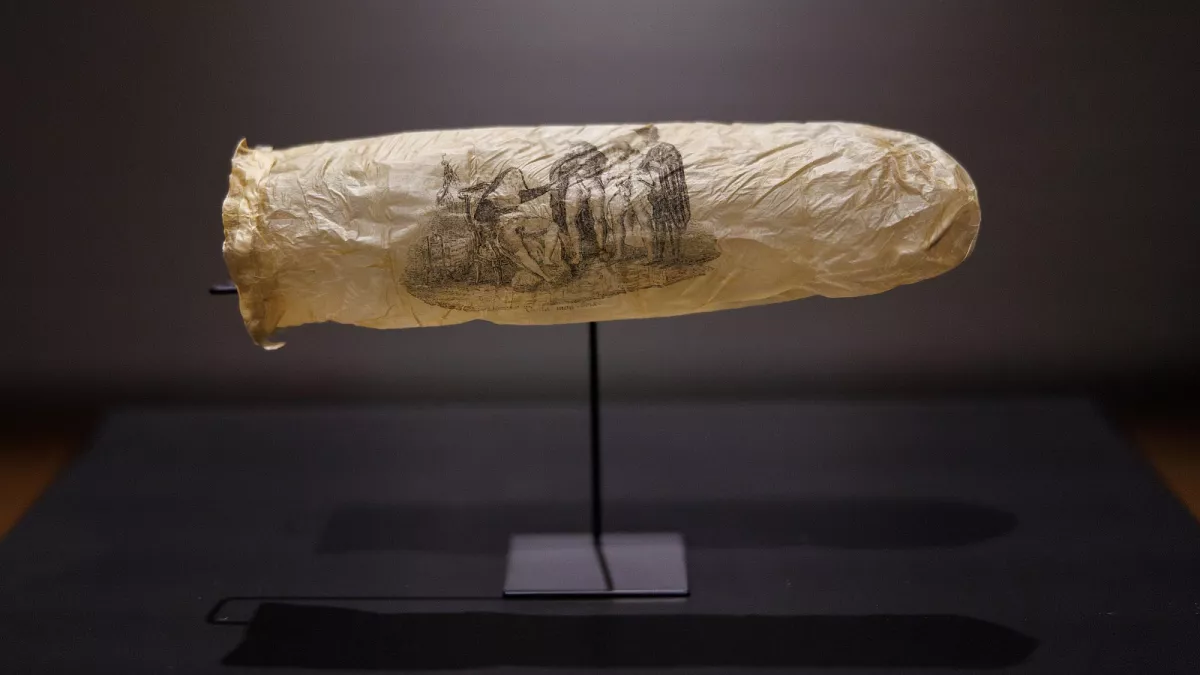

In a move that blends art history, social commentary, and a hint of scandal, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has unveiled one of its most curious acquisitions to date—a 200-year-old condom. Likely crafted around 1830 from a sheep’s appendix, this artifact has drawn attention not merely for its age or material, but for its shocking and complex artwork.

Engraved with an erotic scene that features a nun and three clergymen, the condom is now on display as part of the museum’s new exhibition Safe Sex?, which explores themes of sex work and sexual health through historical prints and drawings from the Dutch and French artistic traditions.

The condom, purchased at an auction in Haarlem for €1,000, marks a significant departure from typical museum artifacts. It’s a piece of material culture that speaks volumes about societal attitudes, sexuality, religion, and class during the 19th century.

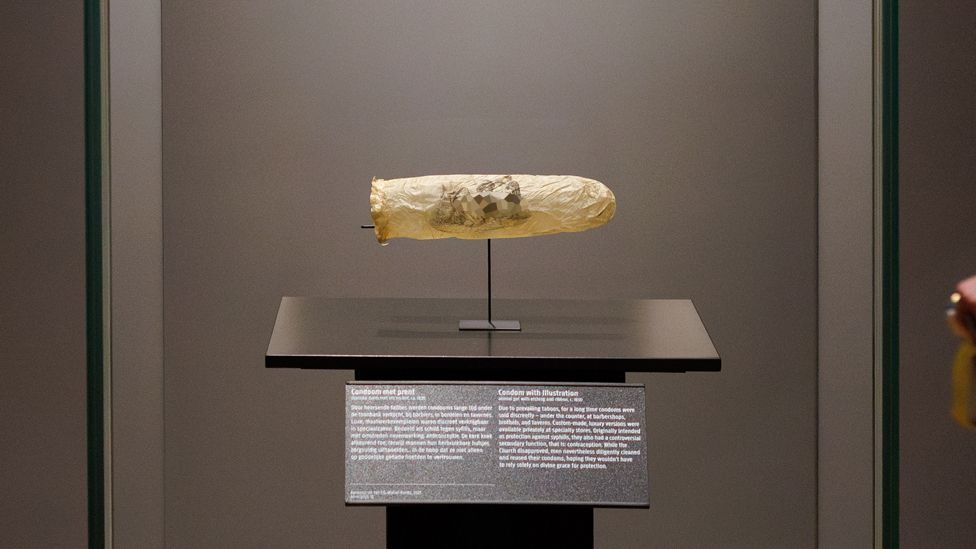

Displayed in a glass case and illuminated for close inspection—including under ultraviolet light—the item has quickly become the centerpiece of the exhibition, raising eyebrows, questions, and discussions about the intersection of intimacy, morality, and art.

A Souvenir from the Shadows of Parisian Brothels

According to Rijksmuseum curator Joyce Zelen, the condom likely originated from an upscale brothel in Paris. During the early 19th century, France—particularly its capital—was a hub of both artistic innovation and clandestine sensuality.

Brothels operated within a spectrum of legality and social acceptance, often doubling as places where the upper classes could explore pleasures unacknowledged in polite society. The featured condom seems to embody this duality: a medically ineffective, yet ornately designed item, intended less for practical use and more as a risqué novelty or souvenir.

Measuring 20cm in length, the condom is engraved with a provocative etching. A partially undressed nun gestures toward the erect genitalia of three distinct clergymen—one bald, one thin, and one slightly overweight—alongside the caption “Voila, mon choix” (“There, that’s my choice”).

Read : What is Digital Condoms? Here’s All You Need to Know

This alludes to the mythological Judgment of Paris, where the Trojan prince must choose the fairest goddess. Zelen interprets this as evidence of the object’s intellectual depth, suggesting its original owner was someone with a classical education and a taste for layered, allegorical humor.

A 200-year-old condom, adorned with an erotic etching of a nun and clergymen, is now displayed at the Rijksmuseum, challenging perceptions of 19th-century sexuality and satire. pic.twitter.com/kpWGbnq8es

— Ancient Origins (@ancientorigins) June 5, 2025

Interestingly, despite the subject matter, there is no definitive evidence that the condom was ever used. UV light inspection revealed no signs of wear, perhaps affirming its role as a decorative or collectible piece rather than a functional contraceptive. Its preservation further underscores how it may have been valued as a luxury item—part curiosity, part art, and part provocation.

Sexual Morality, Satire, and Religion

What makes this exhibit particularly potent is the way it captures the tension between religious doctrine and sexual freedom. In the 1830s, both the Catholic and Protestant churches maintained strict prohibitions against contraception and sexual activity outside of marriage. Condoms, when available, were frequently condemned from the pulpit. Nevertheless, they were available—often sold “under the counter” in brothels, barber shops, or discreet apothecaries.

By depicting a nun and clergymen in such an explicitly sexualized context, the condom’s artwork serves as a satirical critique of religious hypocrisy. It teases at the forbidden, suggesting the gap between moral preaching and private behavior. For museum-goers today, it may evoke thoughts about the timeless nature of institutional contradictions and the enduring human fascination with the taboos of sex and sanctity.

This artifact also invites consideration of early advertising methods. Zelen remarked that the engraving’s ambiguity was intentional: viewers cannot definitively say which of the three men the nun is choosing. As such, the condom’s design allows any male observer to feel as though they, too, could be the “chosen one.” In a modern context, this mirrors marketing strategies where consumers are personally flattered or targeted to evoke a sense of desire or belonging.

From Sheepskin to Safe Sex: The Evolution of Contraception

The presence of this condom in a prestigious art museum also raises interesting points about the history and development of birth control. Before vulcanized rubber was invented in 1839 by Charles Goodyear, condoms were far from effective. Materials like linen, animal intestines, and even turtle shells were employed to create sheaths that offered little more than psychological assurance. They were reused, fragile, and often difficult to acquire.

The 1830s marked a time when the idea of “safe sex” was in its infancy, more a whispered suggestion than a public health policy. Syphilis, gonorrhea, and other sexually transmitted infections were widespread, but knowledge about how to prevent them was limited, especially among the general population. Medical texts often avoided discussing contraception, and public discourse shunned the topic entirely.

With the industrial revolution and the later development of rubber, contraception slowly became more reliable and accessible. But the early artifacts—such as the one now housed at the Rijksmuseum—highlight how long human beings have attempted to balance desire, protection, and discretion. This sheep appendix condom is not just a curiosity; it’s a relic from a time when sexuality was both dangerous and exhilarating, hidden yet omnipresent.

The museum’s Safe Sex? exhibition addresses these broader narratives by contextualizing the condom within a series of Dutch and French prints that span several centuries. These artworks tackle subjects like sex work, venereal disease, and the social regulation of intimacy, presenting a rich tapestry of human behavior that challenges sanitized versions of history.

While some may raise eyebrows at the museum’s choice to include a condom in its collection of fine art, others will appreciate the boldness of embracing such material culture. As Zelen explains, art is not always about beauty—it’s about meaning, challenge, and relevance. The 1830 condom accomplishes all three.

By placing it alongside Dutch golden age masterpieces, the museum makes a statement about what deserves to be remembered, studied, and displayed. This act of inclusion asserts that sexual history—like military history, religious history, or artistic evolution—is integral to our understanding of the past.

Moreover, it reminds us that people in every era have grappled with the same desires, boundaries, and contradictions. Whether dressed as a nun pointing to her preferred clergyman or hidden in the back room of a brothel, the stories we tell about sex reveal much about who we are as societies.

Ultimately, the condom serves not only as a humorous, risqué artifact but as a doorway into deeper discussions. It is about pleasure and protection, about art and anatomy, about shame and sophistication. Through this single object, viewers are invited to reflect on the ways we depict—and often deny—our most intimate truths.

In curating and displaying this extraordinary piece, the Rijksmuseum invites its visitors to confront the intersections of history, sexuality, and expression. And in doing so, it challenges the conventional borders of museum curation, reminding us that human experience is vast, layered, and often delightfully scandalous.